А. КОРО Стена и холст: пространственные эксперименты Эль Лисицкого и белый куб

СТЕНА И ХОЛСТ: ПРОСТРАНСТВЕННЫЕ ЭКСПЕРИМЕНТЫ ЭЛЬ ЛИСИЦКОГО И БЕЛЫЙ КУБ

УДК 038+7.038.55

Автор: Коро Анастасия, Студент магистратуры, Факультет истории искусства, Университет Кингстона, e-mail: anastasiakoro@gmail.com

Аннотация: В своей статье 1976 года «Заметки о галерейном пространстве» Брайан О'Доэрти предложил теорию комплексного развития понятия белого куба вместе с развитием современного пространственного искусства. Он обосновывает свою теорию, анализируя переход от пространства живописного салона к белому кубу и от масляного письма к искусству инсталляции. Главный принцип такого перехода – сдвиг от двухмерного к трехмерному пониманию в искусстве. Несмотря на то, что такой переход к трехмерному пониманию было одним из главных предметов работы русских авангардных художников, О'Доэрти об этом не упоминает, вероятно, из-за недостатка информации о них в период Холодной войны. В нашей статье мы применяем теорию О'Доэрти к пространственным экспериментам русского художника-авангардиста Эль Лисицкого, для чего подробно анализируем «проуны» Лисицкого, его проун-комнату и абстрактный кабинет в сравнении с белым кубом. Анализ тезисов и их обоснования О'Доэрти позволяет поставить вопрос: применимо ли все это к творчеству отдельного художника. В то же время появляются основания утверждать, что критический язык О'Доэрти вполне применим для осмысления влияния Лисицкого на современное понимание пространства в искусстве. Результат такого анализа может быть распространен и на достижения других русских авангардистов, занимавшихся пространственными экспериментами в искусстве.

Ключевые слова: русский авангард, белый куб, Лисицкий, О'Доэрти, пространство, инсталляция, трехмерное понимание в искусстве

THE WALL AND THE CANVAS: LISSITZKY’S SPATIAL EXPERIMENTS AND THE WHITE CUBE

UDC 038+7.038.55

Author: Koro Anastasia, МА student, Art History Department, University of Kingston, e-mail: anastasiakoro@gmail.com

Summary: In his essay ‘Notes on the Gallery Space’ (1976), Brian O’Doherty suggests a theory of integral development of the concept of the White Cube and contemporary space-related art. He explains the theory by analyzing the transition from the Salon hanging to the White Cube and from the easel painting to installation art. The general principle of this transition is the shift from two-dimensional to three-dimensional concepts in art. Despite the fact that the transition to three-dimensional concept in art was one of the key subjects of experimental work of Russian avant-garde artists, O’Doherty omits it in his analysis possibly due to the lack of the information during the Cold War period. This essay applies O’Doherty’s theory to the spatial experiments of Russian avant-garde artist El Lissitzky; it does this via a consecutive study of Lissytzky’s Prouns, Proun Room and the Abstract Cabinet in relation to the concept of the White Cube. An analysis of O’Doherty’s claims and reasoning is undertaken and the question asked: are they valid in the context of a specific artist? At the same time it is suggested that the critical language of O’Doherty could be used to reassess Lissitzky’s impact on the contemporary concept of space in art. The result of this analysis could be applied to the work of other Russian avant-garde artists engaged with spatial experiments in art.

Keywords: Russian avant-garde, White Cube, Lissitzky, O’Doherty, space, installation, three-dimensional concept in art

Ссылка для цитирования:

Koro А. The wall and the canvas: Lissitzky’s spatial experiments and the white cube // Артикульт. 2014. 13(1). С. 26-36.

New space neither needs nor demands pictures - it is not a picture transported on a surface. This explains the painter’s hostility towards us: we are destroying the walls as the resting place for their paintings.

El Lissitzky, Proun Room, 1923.1

Now a participant in, rather than a passive support for the art, the wall became the locus of contending ideologies; and every new development had to come equipped with an attitude toward it.

Brian O’Doherty, Notes on the gallery space, 1976.2

The contemporary viewer is preconditioned to experience art in a certain type of exhibition space - a large empty room with white walls where paintings have a generous amount of space around them. This type of gallery space has been named the White Cube. In his essay ‘Notes on the Gallery Space’ (1976)3 Brian O’Doherty suggested a theory of the emergence of the White Cube which he linked to the introduction of the concept of three-dimensional space in painting.

This research aims to place the spatial experiments of Russian Constructivist artist El Lissitzky in the context of the theory of Brian O’Doherty. How was space conceptualized by Lissitzky? What was the nature of his criticism of classical perspective and easel painting? How did he develop his awareness of the space around the painting? How did his work contribute to the establishment of the White Cube? If the concept of the White Cube had not been available to him, how might he have used the gallery space? The critical language of O’Doherty offers a framework which is highly relevant to the analysis Lissitzky’s discoveries on the path towards a contemporary concept of space in art.

This essay comprises three parts that consecutively explore the works of El Lissitzky: the Proun paintings, the Proun Room and the Abstract Cabinets in relation to specific aspects of the emergence of the White Cube. The study of the Proun paintings focuses on the concept of perspective and focal point on the plane; the next section, on the Proun Room, explores how Lissitzky treated the problem of active engagement of the viewer with an artwork; and the final section discusses the perplexing question of the gallery space as part of art experience that was resolved by Lissitzky in his Abstract Cabinets. The transition to the White Cube was complete when certain aspects of Salon exhibitions and easel painting had been entirely abandoned. This project will show that Lissitzky never abandoned these aspects but rather made an attempt to reinvent them. He did not reach the contemporary understanding of the White Cube. Nevertheless his work became an iconic example of an early installation work.

In his essay ‘Notes on the Gallery Space’ Brian O’Doherty argues that we see contemporary art through the White Cube; the interior of the gallery and the arrangement of paintings is now vital for understanding the art, as if it has become part of the pictorial composition itself. He suggests a consistent theory on the emergence of the White Cube which is related to the reassessment of classical perspective in easel painting. In the course of the gradual disappearance of the focal point in painting - through the introduction of horizons; the unfocused or blurred shapes of impressionist paintings; and eventually photography, where cropping becomes part of composition, the standards of representation become unstable. The edge, the wall and eventually the whole space that surrounds an artwork becomes conceived as a part of the pictorial composition. The relocation of the viewer’s attention from observing perspective on the picture plane to experiencing a real space can be described in general as a transition from a two-dimensional to a three-dimensional concept of space in painting.

At the dawn of the twentieth century this transition from two-dimensional pictorial form (easel painting) to a spatial one (three-dimensional construction) was one of the key subjects of the experimental work of Russian avant-garde artists of the 1920s. It was carried out according to the idea that art could change social life. The artists believed that the artist had to abandon easel painting in favor of designing everything that constitutes the life of a human being, from clothing to urban planning. The new objective environment was to change the condition of the human mind and way of life according to the socialist notion of the future. This included new demonstration spaces for modern art that would change the way art would be exhibited, experienced and understood4.

El Lissitzky was one of the Russian constructivist artists who completed the journey from painting to three-dimensional space. Trained as an engineer and later becoming a graphic designer, he turned his attention to exploring interconnections between painting and architecture. The spatial experiments of Lissitzky were accomplished in two stages: the transformation of classical perspective on the picture plane and the construction of three-dimensional installations. In 1921 he created a series of graphic works called Prouns - Projects for Asserting the New - that examined possibilities of representation of irrational and imaginary spaces on the plane. When all possibilities of two-dimensional representation were exhausted, Lissitzky created a three-dimensional Proun, called Proun Room which was presented at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition in 1923. In 1926 he created the Abstract Cabinet as a privileged exhibition space for abstract art that radically differed from the traditional exhibition spaces of the nineteenth century5.

In the course of his experiments Lissitzky made major advances towards the understanding of space, in its own right, as a theme in art and explored new possibilities of exhibiting. His demonstration rooms differed from contemporary galleries but at the same time represented a phase in the transition to three-dimensional space in painting and to the emergence of the White Cube.

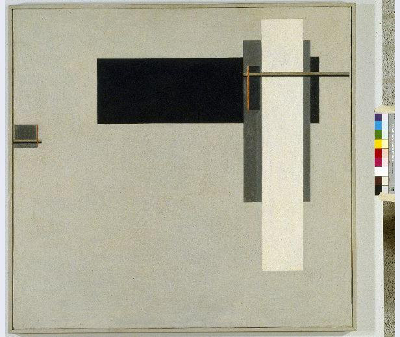

Fig. 1 El Lissitzky, Proun G.B.A. (1923), oil on canvas, 82.9 x 84.9 cm, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

1.THE PROUNS

According to Brian O’Doherty the reassessment of classical perspective was crucial to the transition to the concept of the White Cube. The criticism of classical perspective was a starting point for Lissitzky’s spatial experiments and was expressed in an essay on Art and Pangeometry in 19256.

Brian O’Doherty describes the emergence of the White Cube by comparing it to the Paris Salons, art exhibitions of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The two kinds of art exhibitions were diametrically different in how the artwork was displayed. O’Doherty argues that this difference depended on how space was represented in the paintings7.

The Salon hanging was designed to exhibit easel paintings that represented the illusion of space created by means of direct one point perspective. The viewer was supposed to dive into this illusion and lose the sense of the real space of the gallery. The paintings could be hung in rows close to each other as one visual illusion was protected from another by a heavy frame and the real space would not interfere with the visual experience.

In contrast, the White Cube gallery seems to be an inverted version of the Salon. Because the accurate representation of perspective on the picture plane is no longer as important, the viewer‘s eyes are not entirely fixed on the content of the painting and he is aware of a painting as an object in space. The arrangement of paintings in a gallery forms a consistent whole with the pictorial composition, and makes a significant and inseparable impact on the perception of the qualities of modern artwork. According to O’Doherty the disappearance of perspective and the focal point of the paintings was inevitable for the development of the art. He does not explain the exact reasons for the decline of perspective but only notes that otherwise art ‘would become obsolete’8.

For Lissitzky the break of classical perspective was a conscious decision. In her study of the concept of fourth dimension and non-Euclidian geometry in modern art Linda Dalrymple Henderson explains how he arrives at this point through analysis of irrational numbers in mathematics that had their connection to the idea of space9. Lissitzky suggests an artist could work with irrational spaces just as mathematician were doing at that time. Starting his artistic career in the studio of Kazimir Malevich who had been working on Suprematist paintings, Lissitzky decides to apply his concept of irrational space to Malevich’s geometric abstractions10. In 1919 he pained his first Prouns where he depicted quasi-three-dimensional space that Dalrymple Henderson describes as ‘impossible overlappings and interconnections, tendency of forms to fluctuate back and forth’11. Lissitzky not only considers how to create abstract space on the plane but also how make this space dynamic and stimulate active engagement of the viewer with painting. In his essay ‘A. [Art] and Pangeometry’ he compares classical and reverse perspective of traditional Chinese paintings and Russian icons12. In the latter, the focal point and the position of the observer switch places which gives an illusion of observing the painting from inside. Lissitzky assumes that if the space displayed on the plane contained numerous focal points it would allow the observer to enter the painting and travel through this multidimensional space imaginatively. Selim Khan-Magomedov notes that the abstract shapes of the Prouns not only create an illusion of reality but a logical assumption of space endlessly changed by the intervention of the viewer, thus transforming the observer into participant13.

Barrett Watten gives a brief summary of the wide range of Lissitzky’s achievements in Prouns: ‘Overturning of Western perspective, the transcendence of the picture plane, simultaneity of all colors within the spectrum of white, integration of temporality into spatial form, production of imaginary space through rotation, a-material materiality’14.

In order to construct a consistent theory of transition to three-dimensional concept in painting O’Doherty describes how perspective disappears from impressionist paintings; how the expressionists start to conceptualize the frame and the edge of a painting; and how photography makes ‘the location of the edge a primary decision as it composes - decomposes - what it surrounds’. According to O’Doherty, Cubism, however, falls out of this system:

What a conservative movement Cubism was. It extended the viability of the easel picture and postponed its breakdown. [...] Cubism’s concept of structure conserved the easel painting status quo; Cubist paintings are centripetal, gathered towards the centre, fading out toward the edge15.

From this point of view perhaps even Lissitzky could be called conservative since as, Khan-Magomedov notes, Lissitzky’s Prouns were an attempt to discover possibilities of space within the picture plane, without turning flatness into volume16.

However, although Lissitzky did not lose the focal point on his paintings, we cannot say that he conserved easel painting. His plan was to go beyond picture plane. In his essay Lissitzky, like O’Doherty, explores how perspective was reassessed by different artists and agrees that the impressionists ‘…Were the first to begin exploding the hereditary notion of perspectival space’. But unlike O’Doherty, Lissitzky believed Cubism to be another progressive stage in this process. He argued that ‘[Cubists] build from perspective plane forward into space’, meaning that they look as if depicted shapes are stepping out of the painting into the real space17.

Contrary to the theory of O’Doherty, Lissitzky does not abandon perspective in his paintings but reinvents it by depicting abstract, irrational or imaginary spaces, yet it does not prevent him from transitioning into three-dimensional space. It is significant that his reasons for this transition were not only the desire for further artistic experiments but also ideological. Paul Wood explains that constructivist artists ‘abandoned the conventional sense of artistic work to participate in development of new forms of community’ to achieve a goal of new socialist society18. And this was surely a motivation for Lissitzky. As he writes: ‘Proun begins at the level of surface, turns into a model of three-dimensional space, and goes on to construct all objects of everyday life’19.

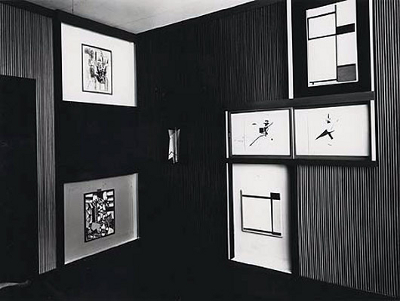

Fig. 2 El Lissitzky, Reconstruction of the Proun Room (1923), (1971), painted wood, 320 x 364 x 364 cm, Van Abbemuseum

2. THE PROUN ROOM

Lissitzky described his Prouns as ‘an interchange station between painting and architecture’20. He considered them to be laboratory work in preparation for a leap from canvas to real space. In a letter Lissitzky writes to one of the organizers of his exhibition: ‘You would be treating the problem in quite the right manner, as prescribed by common sense, if you wanted to order a cupboard for these documents of my work’21. Yve-Alain Bois notes that this indicates the utilitarian attitude of Lissizky to his works as if they were blueprints that had to be stored horizontally and had no artistic value unless turned into three-dimensional objects22. In 1923 Lissitzky made an attempt to extract the content of his paintings when he created the three-dimensional Proun Room for the Great Berlin Art Exhibition. If the Proun paintings suggested that the viewer could enter the depicted space imaginatively by observing the images, the Proun Room gave him/her an opportunity to physically do so.

The Proun Room is an interior with abstract geometric shapes arranged across the white walls of a relatively small room. The large black and grey blocks were painted directly on the walls and the wooden details were fixed over them. The Proun Room is reminiscent of a mural with three-dimensional elements. The arrangement of the objects created a certain rhythm and directed the attention of the observer from one object to another. According to Eva Forgacs the Proun Room was a painting which ‘aspired towards totality by integrating visual, spatial, and temporal experiences and by creating an unbroken rhythmic sequence of interrelated forms and colors in the real, breathing space of a room’23.

On one hand, the structure of the Proun Room possessed the formal qualities of the White Cube as described by O’Doherty with plain walls, no windows and light coming from the ceiling - the room was ‘unshadowed, white, clean and artificial’24. The artwork was released from the frame and consciously arranged on the walls by the artist. The artist created the context for his own work. On the other hand, when describing how we experience contemporary art O’Doherty notes that: ‘We have now reached a point where we see not the art but the space first’25 and in the Proun Room our attention is clearly attracted by the objects while the space of the room is something that obstructs and blocks our appreciation of it. The contemporary viewer would probably have felt that the room is too small and would have wanted to push the walls apart. In this way it significantly differs from the White Cube.

There are three ways in which the Proun Room deviates from the White Cube. The first one was described by Yve-Alain Bois who notes that in the Proun Room objects dominate over the space and suggests that Lissitzky physically escapes the picture plane but keeps the old purpose of easel painting26. In painting the sense of space on the plane, created by means of classical perspective, is defined by depicted objects that serve as markers of scale, distance and location of focal point. Without these markers space cannot be represented. Lissitzky automatically transfers the content of his paintings to the walls without considering its relationship to the proportions of the room. He transfers objects into the room but the space as such is not a subject of his work.

In his memoirs Sergey Eisenstein recalls his impression of the first Suprematist project that endeavored to modify the streets of a Russian town Vitebsk by paining Suprematist compositions on the buildings as decorations27. This, of course, could not fundamentally alter the appearance of the streets, which could only be accomplished by actually constructing the buildings according to principles of Suprematism. Eisenstein described his impression of Vitebsk as ‘Suprematist confetti strewn about the streets of an astonished town’28, meaning that the changes were insubstantial. It could be argued that by attempting to decorate the surface of the room without reinventing the concept of the space as such Lissitzky accomplished the task of reinventing exhibition space to the same extent that Malevich achieved his aims in Vitebsk. This would certainly be a view supported by O’Doherty. And this is the second way in which the Proun Room differs from the WhiteCube.

The third difference between the Proun Room and the White Cube is the arrangement of the objects that directs the gaze of the observer. According to the reading of Victor Margolin ‘the lines of force on each wall... were seemingly presented with the expectation that the room’s inhabitant would experience the walls sequentially’29. One would have to start observing the the right wall of the Proun Room from the black rectangular shape at the bottom, follow the wooden plank that lead the eyes to the composition on the central wall. The black shapes on the central wall would hold our attention, which would then shift diagonally down to the yellow ball and the cross. Finally another wooden plank would direct the gaze towards the black rectangular shape and an abstract composition fixed at the end of it. The Proun Room makes an overall impression of a perfectly staged performance. Like an exhibition guide Lissitzky takes the viewer by the hand and walks along his artwork explaining where exactly and for how long he should look at it. The defined rhythm of the Proun Room, along with the small size of the room, has a restrictive effect on the viewer and with no opportunity to wander around the feeling of freedom and fluidity of space evoked by the Proun paintings, is absent. Even though Lissitzky escapes the trap of perspective and picture frame, he continues working within the paradigm of easel painting.

One could say that that the Proun Room remained an easel picture recreated in real space. Although Lissitzky abandoned the limits of the picture frame and managed to overcome the conventional medium of painting by creating a three-dimensional installation, the Proun Room had not become a site-specific work. Lissitzky adheres to the principle of constructing space by forming the objects that define it, instead of conceptualizing the space as such. But he reinvents this principle, using the walls as a canvas and placing his objects on these. In addition, the fixed position in front of the painting, the sense of control that perspective imposes on the viewer receives a new interpretation in Proun Room. Instead of creating one focal point on the plane Lissitzky invents a system of visual management where the viewer’s attention travels from one object to another according to the intention of the artist. The Proun Room remains a highly controlled environment, trembling on the edge of the White Cube the Proun Room is held back by the conventions of classical painting.

Fig. 3 El Lissitzky, Reconstruction of The Abstract Cabinet (1928), (1968), medium, dimensions unknown, Sprengel Museum

3. THE ABSTRACT CABINET

In the same way that Lissitzky was challenging conventional art of the times he was also unsatisfied with the way art work was exhibited. In a letter addressed to one of the curators who had to put up the Proun paintings Lissitzky expressed a bitter irony regarding the suggested exhibition space: ‘You go on [sic] enquire on which wall you should hang my work. The floor is laid with carpets and moulded cupids are flying around on the ceiling. When I made my Proun, I did not think of filling one of these surfaces with yet another decorative patch’30.

In his paintings Lissitzky looked for ways to represent the dynamic space and stimulate the viewer’s active engagement with the artwork. He believed that the exhibition spaces for his Prouns had to express similar qualities. The conventional exhibition spaces based on the principle of Salon hanging were not capable of achieving this goal. The conflict between the aspiration for the dynamism in the avant-garde paintings and the existing means of exhibiting made Lissitzky look for new ways of communicating modern artistic ideas.

Lissitzky’s dissatisfaction with the Salon hanging echoes the pejorative notion of O’Doherty that, in French Salons, masterpieces were hung as wallpaper. O’Doherty explains that ‘each picture was seen as a self-contained entity, totally isolated from its slum-close neighbor by a heavy frame around and a complete perspective system within’31. This mode of exhibition had a paralyzing effect on the viewer and his role was reduced to that of a passive consumer of the illusion of the space represented in the painting. In contrast the White Cube gallery offers a vast territory for each painting and opportunity for the viewer to engage with each artwork individually. It was only with the disappearance of perspective from the picture plane that the wall became ‘a participant in, rather than support for the art’ and ‘modified anything shown on it’32.

Lissitzky made an attempt to shatter the conventions of Salon hanging by designing a privileged exhibition space for abstract paintings. He was commissioned to design the Room for Constructivist Art for Art Exhibition in Dresden in 1926, and the Abstract Cabinet for the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover in 1927–2833.

The structure of both cabinets was similar apart from the slight changes in building materials, which are not significant for this research. In this work Lissitzky invented several devices aimed at destabilizing the monumental structure of a standard museum. The walls were decorated with a lath system, the sides of the wooden panels were painted in black and grey. It created an optical illusion that the wall was changing color depending on the viewpoint of the observer. The paintings were hung against backgrounds made of panels of various materials and textures which had to highlight the pictorial qualities of the paintings. Moving panels allowed the visitors to see paintings behind them and engage with the exhibition space. These inventions aimed to destabilize the stiff environment of the museum and stimulate audience mobility and visual involvement of the observer with the artwork and the exhibition space itself. Yet Lissitzky does not answer the question that O’Doherty considers crucial for the White Cube: ‘how much space [...] should a work of art have to breathe?’34

So, while Lissitzky managed to change the standard Salon hanging still the result did not bear any resemblance to the White Cube. Maria Gough ironically calls the Abstract Cabinets ‘another kind of wall-to-ceiling drama’35 meaning that for a contemporary viewer this space is as hard to digest as the Salon hanging due to its overloading with artwork and interior design features.

O’Doherty’s notion that in the White Cube gallery ‘a participant in, rather than support for the art, the wall became the locus of contending ideologies’36 should rather be read metaphorically. Lissitzky literally activates the wall and turns it into a part of an installation. O’Doherty writes that in a contemporary gallery space ‘works of art conceive the wall as a no-man’s land on which to project their concept’37. In the Abstract Cabinets the wall is not subordinate to an artwork but conversely has an overwhelming impact on it. Together they form one communicating system and are equally important in producing meaning. Lissitsky designated a certain place for each artwork rather than suggesting a territory for it which contradicts another of O’Doherty’s suggestions that ‘there is a peculiar uneasiness in watching artworks attempting to establish territory but not place in the context of the placeless modern gallery’38.

In his work Lissitzky did not abandon the Salon hanging but looked for ways to reinvent it. Maria Gough suggests that Lissitzky ‘initiates dialogue with the quasi-architectural framework created in the older, salon style museum installations’39. She explains that Lissitzky does not reject the close alignment of paintings but rearranges them in a modern way. He does not reject the embellished interior but conceptualizes it: the lath system represents the structure inside the wall, the beauty of the functional parts of the building. O’Doherty concludes his essay with an example of an installation by William Anastasi at Dawn in New York where ‘surface, mural and wall have engaged in dialogue central to modernism.’ Lissitzky engages in this dialogue as well, by turning the exhibition space into an installation that works with concepts of construction and dynamism, but he does not work with ‘the ocean of space in the middle’40.

At the same time it cannot be claimed that the concept of the White Cube had not been available to Lissitzky. His ideas were developing in parallel with the development of the White Cube. In her essay Gough placed the Abstract Cabinet in the context of the gallery space where it had been presented originally - the Internationale Kunstausstellung. Photographs of the gallery interiors designed by Heinrich Tessenow clearly remind us of a contemporary museum and can be called a prototype of the White Cube. Gough observes that:

...hung with paintings in a single tier at the viewer’s eye level on a calm, neutral grey background, Tenessow’s enfilade of sober galleries, stripped of ornament other than their elegant geometry, superseded the traditional salon-style carpeting of walls with paintings from floor to ceiling41.

O’Doherty notes that at the final stage of the development of White Cube artists were joined by dealers and curators. ‘How they - in collaboration with the artist - presented these works, contributed, in the late forties and fifties, to the definition of the new painting’42. In the cases of Lissitzky and Tessenow we witness the moment when the White Cube and installation met but did not recognize each other.

In an essay written in 1970, Brian O’Doherty advocated site-specific installation art by tracing the modern system of display now known as the White Cube. He argues that the White Cube became an arena for the new mode of artistic practice which embraced the relation of painting to three-dimensional space. He also posits that the White Cube emerged as a result of the inner logic of the development of modern painting rather than due to external practical circumstances, such as the evolution of architecture. He explains the nature of this logic as following the disappearance of classical perspective from the plane which made its content shallow. As the content of the paintings became conceptually exhausted artists had to hijack undiscovered territories that were lying in the domain of real space. The reassessment of the illusive space of the plane led to a new awareness of the real space around the painting. For O’Doherty this transition from a two-dimensional to a three-dimensional concept in painting was an inevitable stage in its development and prevented art from becoming obsolete. The result of ‘transposition of perception from life to formal values’ was that context became the new content of painting. O’Doherty calls this transposition ‘one of the modernism’s fatal diseases’43.

It seems that the fatal disease of modernism had not yet affected the spatial experiments of Lissitzky at that time. While he succeeded in removing it from the picture frame, he continued to work with the content of the painting in three-dimensional space rather than with the context. In the Proun paintings he does not abandon classical perspective but invents an original way of representing illusive spaces through the introduction of several focal points. The Proun Room was the first attempt to deploy the content of the Proun paintings into the gallery space. It was accomplished by literal transition of the subject of the paintings onto the walls without initiating a dialogue between the artwork and the wall and the dimensions of the gallery. And the key factor here is the direction of the expansion: while O’Doherty describes the lateral expansion of the painting, Lissitzky built forward into the space. Lissitzky reinvents the Salon exhibition space by introducing new building materials, new ways of arranging of the artwork. To interpret Lissitzky only through the framework of the White Cube would be a reduction. He never abandoned the concepts that were available to him at that time but reinvented them, which contributed to the development of concept of three-dimensional space in installation art, interior design and architecture.

O’Doherty suggests a linear theory of development of the White Cube: the concept of three-dimensional space was first developed by the artists and taken further by dealers and curators. Via the example of Lissitzky’s Abstract Cabinet and Tessenow’s Internationale Kunstausstellung we can see how the concept of space in art and in exhibiting were developing separately in parallel to each other.

ЛИТЕРАТУРА

1. Bois, Yve-Alain. Axonometry, or Lissitzky’s Mathematical Paradigm // El Lissitzky, 1890-1941: Architect, Painter, Photographer, Typographer / еd. J. Debbaut, M. Soons. Eindhoven: Municipal Van Abbemuseum, 1990.

2. Dabrowski, Magdalena. Contrasts of Form: Geometric Abstract Art 1910-1980. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1985.

3. El Lissitzky, 1890-1941: Architect, Painter, Photographer, Typographer / еd. J. Debbaut, M. Soons. Eindhoven: Municipal Van Abbemuseum, 1990.

4. Forgacs, Eva. Definitive Space: the Many Utopias of El Lissitzky’s Proun Room // Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow, / ed. by N. Perloff, B. Reed. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003.

5. Gough, Maria. Constructivism Disoriented: El Lisstizky’s Dresden and Hannover Demonstrationsraume // Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow, / ed. by N. Perloff, B. Reed. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003.

6. Henderson Dalrymple, Linda.The Fourth Dimension and Non-Eucledian Geometry in Modern Art. Cambridge, Engalnd; London, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013.

7. Khan-Magomedov, Selim Omarovich. Pioneers of Soviet Architecture: the Search for New Solutions in the 1920s and 1930s. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

8. Lissitzky-Kuppers, Sophie. El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts. London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968.

9. Lissitzky, El. A. and Pangeometry. // S. Lissitzky-Kuppers. El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts. London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968.

10. Lissitzky, El. Proun Room, Great Berlin Art Exhibition // S. Lissitzky-Kuppers. El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts. London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968.

11. Margolin, Victor. The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917-1946. Chicago; London; University of Chicago Press, 1997.

12. Milner, John. El Lissitzky Design. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2009.

13. O’Doherty, Brian. Inside the White Cube. The Ideology of the Gallery Space. Berkley; London: University of California Press, 1999.

14. Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow / ed. Perloff, Nancy, Reed, Brian. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003.

15. The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932 / ed. Wood, Paul New York; Frankfurt: Guggenheim Museum; Schim Kunsthalle, 1992.

16. Watten, Barrett. The Constructivist Moment: From Material Text to Cultural Poetics. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2003.

REFERENCES

1. Bois, Yve-Alain, ‘Axonometry, or Lissitzky’s Mathematical Paradigm’ in J. Debbaut, M. Soons (ed.), El Lissitzky, 1890-1941: Architect, Painter, Photographer, Typographer (Eindhoven: Municipal Van Abbemuseum, 1990)

2. Dabrowski, Magdalena, Contrasts of Form: Geometric Abstract Art 1910-1980 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1985)

3. Debbaut, Jan, Soons, Marielle (ed.), El Lissitzky, 1890-1941: Architect, Painter, Photographer, Typographer (Eindhoven: Municipal Van Abbemuseum, 1990)

4. Forgacs, Eva, ‘Definitive Space: the Many Utopias of El Lissitzky’s Proun Room’ in Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow, ed. by N. Perloff, B. Reed (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003)

5. Gough, Maria, ‘Constructivism Disoriented: El Lisstizky’s Dresden and Hannover Demonstrationsraume’ in Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow, ed. by N. Perloff, B. Reed (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003)

6. Henderson Dalrymple, Linda, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Eucledian Geometry in Modern Art (Cambridge, Engalnd; London, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013)

7. Khan-Magomedov, Selim Omarovich, Pioneers of Soviet Architecture: the Search for New Solutions in the 1920s and 1930s (New York: Rizzoli, 1987)

8. Lissitzky-Kuppers, Sophie, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968)

9. Lissitzky, El, ‘A. and Pangeometry’, in S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968)

10. Lissitzky, El, ‘Proun Room, Great Berlin Art Exhibition’, in S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968)

11. Margolin, Victor, The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917-1946 (Chicago; London; University of Chicago Press, 1997)

12. Milner, John, El Lissitzky Design (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2009)

13. O’Doherty, Brian, Inside the White Cube. The Ideology of the Gallery Space, (Berkley; London: University of California Press, 1999)

14. Perloff, Nancy, Reed, Brian (eds.) Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003)

15. Watten, Barrett, The Constructivist Moment: From Material Text to Cultural Poetics (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2003)

16. Wood, Paul (ed.), The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932 (New York; Frankfurt: Guggenheim Museum; Schim Kunsthalle, 1992)

List of illustrations:

Fig. 1 Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, Berlijn, Compositie (Proun GBA) <http://www.gemeentemuseum.nl/en/collection/item/4099> [ accessed 06 January 2014]

Fig. 2 Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Prounenraum (1923), reconstruction 1971 <http://www.vanabbemuseum.collectionconnection.nl...> [accessed 06 January 2014]

Fig. 3 Sprengel Museum, Hanover, Raume in der standigen Sammlung <http://www.sprengel-museum.com/painting_and_sculpture/spaces/index.htm?bild_id=71919666&PHPSESSID=c8952346de6eebbde6d882ccd734b8b1> [accessed 06 January 2014]

СНОСКИ

1 E. Lissitzky, ‘Proun Room, Great Berlin Art Exhibition’, in S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968) p. 361.

2 B. O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube. The Ideology of the Gallery Space, (Berkley; London: University of California Press, 1999) p. 29.

3 Ibid, pp. 13-34.

4 M. Dabrowski, Contrasts of Form: Geometric Abstract Art 1910-1980 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1985), p. 55.

5 J. Debbaut, M. Soons (ed.), El Lissitzky, 1890-1941: Architect, Painter, Photographer, Typographer (Eindhoven: Municipal Van Abbemuseum, 1990) p. 8.

6 E. Lissitzky, ‘A. and Pangeometry’, in S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968) pp. 348-354.

7 O’Doherty, pp. 15-19.

8 O’Doherty, p. 23.

9 L. Dalrymple Henderson, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidian Geometry in Modern Art (Cambridge, Engalnd; London, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013) p. 431.

10 J. Milner, El Lissitzky Design (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2009) pp. 8-15 .

11 Henderson, p. 431.

12 E. Lissitzky, ‘A. and Pangeometry’, in S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968) pp. 348-354.

13 S. O. Khan-Magomedov, Pioneers of Soviet Architecture: the Search for New Solutions in the 1920s and 1930s (New York: Rizzoli, 1987) pp. 63-67.

14 B. Watten, The Constructivist Moment: From Material Text to Cultural Poetics (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2003) p. 75.

15 O’Doherty, p. 27.

16 Khan-Magomedov, pp. 63-67.

17 E. Lissitzky, ‘A. and Pangeometry’, in S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968) p. 349.

18 P. Wood, ‘The Politics of the Avant-Garde’ in The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932, P. Wood (ed.) (New York; Frankfurt: Guggenheim Museum; Schim Kunsthalle, 1992) p. 3.

19 E. Lissitzky, p. 344.

20 S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968) p. 35.

21 E. Lissitzky, ‘A. and Pangeometry’, in S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, El Lissitzky: Life. Letters. Texts, (London: Thames and Hudson, London, 1968) p. 344.

22 Y.-A. Bois, ‘Axonometry, or Lissitzky’s Mathematical Paradigm’ in El Lissitzky, 1890-1941: Architect, Painter, Photographer, Typographer (Eindhoven: Municipal Van Abbemuseum, 1990) p. 32.

23 E. Forgacs, ‘Definitive Space: the Many Utopias of El Lissitzky’s Proun Room’ in Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow, ed. by N. Perloff, B. Reed (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003) p. 47.

24 O’Doherty, p. 15.

25 O’Doherty, p. 14.

26 Bois, pp. 30-31.

27 Forgacs, p. 54.

28 Sergey Eisenstein, as quoted in Forgacs, p. 54.

29 V. Margolin, The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917-1946 (Chicago; London; University of Chicago Press, 1997) p. 67.

30 S. Lissitzky-Kuppers, p. 344.

31 O’Doherty, p. 16.

32I bid, p. 29.

33 M. Gough, ‘Constructivism Disoriented: El Lisstizky’s Dresden and Hannover Demonstrationsraume’ in Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow, ed. by N. Perloff, B. Reed (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003) p. 88.

34 O’Doherty, p. 27.

35 Gough, p. 85.

36 O’Doherty, p. 29.

37 O’Doherty, p. 27.

38 Ibid, p. 27.

39 Gough, p. 105.

40 O’Doherty, p. 34.

41 Gough, p. 85.

42 O’Doherty, p. 27.

43 O’Doherty, p. 15.

О журнале

- История журнала

- Редакционный совет и редакционная коллегия

- Авторы

- Этические принципы

- Правовая информация

- Контакты

Авторам

- Регламент принятия и рассмотрения статьи

- Правила оформления статьи

- Правила оформления сносок

- Правила оформления списка литературы

Номера журналов

- Артикульт-58 (2-2025)

- Артикульт-57 (1-2025)

- Артикульт-56 (4-2024)

- Артикульт-55 (3-2024)

- Артикульт-54 (2-2024)

- Артикульт-53 (1-2024)

- Артикульт-52 (4-2023)

- Артикульт-51 (3-2023)

- Артикульт-50 (2-2023)

- Артикульт-49 (1-2023)

- Артикульт-48 (4-2022)

- Артикульт-47 (3-2022)

- Артикульт-46 (2-2022)

- Артикульт-45 (1-2022)

- Артикульт-44 (4-2021)

- Артикульт-43 (3-2021)

- Артикульт-42 (2-2021)

- Артикульт-41 (1-2021)

- Артикульт-40 (4-2020)

- Артикульт-39 (3-2020)

- Артикульт-38 (2-2020)

- Артикульт-37 (1-2020)

- Артикульт-36 (4-2019)

- Артикульт-35 (3-2019)

- Артикульт-34 (2-2019)

- Артикульт-33 (1-2019)

- Артикульт-32 (4-2018)

- Артикульт-31 (3-2018)

- Артикульт-30 (2-2018)

- Артикульт-29 (1-2018)

- Артикульт-28 (4-2017)

- Артикульт-27 (3-2017)

- Артикульт-26 (2-2017)

- Артикульт-25 (1-2017)

- Артикульт-24 (4-2016)

- Артикульт-23 (3-2016)

- Артикульт-22 (2-2016)

- Артикульт-21 (1-2016)

- Артикульт-20 (4-2015)

- Артикульт-19 (3-2015)

- Артикульт-18 (2-2015)

- Артикульт-17 (1-2015)

- Артикульт-16 (4-2014)

- Артикульт-15 (3-2014)

- Артикульт-14 (2-2014)

- Артикульт-13 (1-2014)

- Артикульт-12 (4-2013)

- Артикульт-11 (3-2013)

- Артикульт-10 (2-2013)

- Артикульт-9 (1-2013)

- Артикульт-8 (4-2012)

- Артикульт-7 (3-2012)

- Артикульт-6 (2-2012)

- Артикульт-5 (1-2012)

- Артикульт-4 (4-2011)

- Артикульт-3 (3-2011)

- Артикульт-2 (2-2011)

- Артикульт-1 (1-2011)

- Отозванные статьи

.png)