M. MADLEN Reimagining Faith: Palestinian Artists Embracing Feminist Discourse through Christian Symbols

REIMAGINING FAITH: PALESTINIAN ARTISTS EMBRACING FEMINIST DISCOURSE THROUGH CHRISTIAN SYMBOLS

Research article

UDC 7.036+75.045

DOI: 10.28995/2227-6165-2024-4-39-50

Received: June 03, 2024. Approved after reviewing: September 18, 2024. Date of publication: December 30, 2024.

Author: Madlen Mahameed, PhD student, St. Petersburg State University of Culture (Saint Petersburg, Russia), e-mail: madlen.m31@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0009-0002-3925-0771

Summary: This article explores the works of four Palestinian artists who incorporate Christian symbols, such as images of saints and religious symbols, into their artwork to critique the patriarchal system of their society. Their use of “quoting” imagery from the lexicon of Christian iconography is a postmodern tactic also seen in feminist art in the West. This approach offers a fresh perspective on how symbols traditionally viewed from a male standpoint can be reinterpreted in a new light. The four female artists analyzed in this study present various forms of critique through their art, utilizing Christian imagery to convey the female perspective, personal narratives, challenges related to sexuality, and themes of female empowerment.

Keywords: Christian symbols, Palestinian art, feminist art, patriarchy, quoting, painting, instillation

ПЕРЕОСМЫСЛЕНИЕ ВЕРЫ: ПАЛЕСТИНСКИЕ ХУДОЖНИЦЫ ВОПЛОЩАЮТ ФЕМИНИСТСКИЙ ДИСКУРС ЧЕРЕЗ ХРИСТИАНСКИЕ СИМВОЛЫ

Научная статья

УДК 7.036+75.045

DOI: 10.28995/2227-6165-2024-4-39-50

Дата поступления: 03.06.2024. Дата одобрения после рецензирования: 18.09.2024. Дата публикации: 30.12.2024.

Автор: Мадлин Махамид, аспирант, Санкт-Петербургский государственный институт культуры (Санкт-Петербург, Россия), e-mail: madlen.m31@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0009-0002-3925-0771

Аннотация: Статья посвящена исследованию творчества четырех палестинских художниц, которые используют христианские символы в свои произведениях, чтобы критиковать патриархальную систему актуального для них общества. Такое использование изобразительных «цитат» из традиционной христианской иконографии – это постмодернистская тактика, которая также встречается в феминистском искусстве на Западе. Этот подход предлагает новый взгляд на то, как символы, традиционно воспринимаемые с точки зрения мужского взгляда, могут быть трактованы в новом свете. Анализируемое творчество четырёх художниц представляет различные формы критики через искусство, в которой христианская символика используется для передачи женского взгляда, личных повествовательных приемов, проблем, связанных с сексуальностью, а также темы женского самоутверждения.

Ключевые слова: христианские символы, Палестинское искусство, феминистское искусство, патриархат, цитирование, живопись, инсталляция

For citation:

Madlen M. “Reimagining Faith: Palestinian Artists Embracing Feminist Discourse through Christian Symbols.” Articult. 2024, no. 4(56), pp. 39-50. (in Russ.) DOI: 10.28995/2227-6165-2024-4-39-50

Introduction

Palestinian art refers to the artwork created by artists who identify themselves as Palestinians, regardless of their location in Europe, refugee camps, the borders of the State of Israel, the West Bank, or Gaza. This art has been produced since the Nakba1 of 1948 up to the present day. Perhaps the most prevalent themes in the works of Palestinian artists include the crisis of dispersion, and the search for the lost homeland. Although lately, it is possible to notice more Palestinian art described in the feminist context, touching on issues related to the female experience in a patriarchal society. Palestinian women experience various forms of colonization: They face challenges as women living under Israeli occupation and militarization, as women living in exile, and as women considered second-class citizens. Both women and men suffer equally from the consequences of the Nakba of 1948. Moreover, Palestinian women often find themselves victims of traditional patriarchal Arab societies, whether they are Christian, Muslim, or Druze.

Patriarchalism in Palestine, like anywhere else in the world, is a system that reinforces male hegemony and hierarchy, perpetuating dualistic stereotypes of women and men to uphold the existing power structure. Though the impact of masculinity is pervasive, its most violent repercussions tend to disproportionately affect women. The feminist discourse in Palestinian art developed not long ago, especially after the nineties along with the openness of female artists to new ideas. Numerous Palestinian artists choose to address pressing issues like honor killing, male domination, and feminist concerns that prominently feature in the final projects of female Palestinian students in art institutions, especially in Israeli Art schools. These themes underscore a societal dilemma wh ere a man's honor hinges on a woman's behavior, risking its integrity should she deviate fr om prescribed norms. The ability of these female artists to present the issues gently and not in a “blatant” way allows the general public to read the works without opposing them despite the revolutionary messages they convey

In Palestinian art, which is highly symbolic, many female artists choose to criticize the patriarchal system through a combination of Christian symbols, such as a cross or figures of saints. In Gannit Ankori's article, she refers to the combination of Christian and Muslim symbols in Palestinian art, claiming that the combination of religious symbols in the art of young Palestinian artists can be seen through a “feminist prism”[Ankori, 2006, p. 390]. It is important to note that in feminist art in general, one of its features is the element of “quoting” that has been used since the 1970s [Dekel, 2011, p. 170]. A good example is the quoting of ancient goddesses and fertility figures from antiquity, such as the goddess Venus or Artemis in their art, and giving them a new interpretation that serves the purposes of their feminist struggle. In the article by researcher Nina Heydemann, she addresses the subject of quoting in art and presents different types of quoting, which are also sometimes referred to as “interpictoriality”, obtained from her research regarding the quotation of Western artists from art history in contemporary works. According to the researcher, the contemporary works that quote Picasso or figures from art history create a new point of view, and they actually “react” to the quoted work. The new work of art does not reproduce or repeat the subject of the work but gives an answer in one way or another [Heydemann, 2021, p. 9]. Although Heydemann's research refers to works of art that quote noted figures from the world of art, such as Vermeer's women or the reconstruction of figures by Velazquez in “Las Meninas”– something that does not occur in the works of art presented in this article, the researcher's opinion is still relevant, as there is a quotation of symbols and iconic figures from Christian art.

In this essay, the quoting is different and is derived from an iconography that primarily represents the male perspective. Especially when talking about religions like Judaism, Christianity and Islam, it is no coincidence that symbols referring to God are masculine because they were actually “discovered” or “revealed” by men [Korte, 2009, p. 122]. In this case, it's important to understand how the ideas of feminist theory, which examine power dynamics, gender relations, and the ways in which patriarchal societies reinforce and perpetuate gender inequality, are present in the feminist criticism of Palestinian artists who incorporate Christian symbols in their work. Through examining the works of four Palestinian artists, the current study will shed light on how they convey their feminist critique through Christian symbols and narratives.

Depicting Saints

One of the Palestinian artists best known for using Christian symbols in her art is Jumana Emil Abboud (b.1971). Abboud was born in the city of Shefa'Amr and later moved to Canada with her parents. At the age of twenty she returned with her family to her traditional hometown, wh ere she encountered the distinct societal pressures faced by women. This experience is depicted in her art, which delves into the identity of the Arab woman. Her artistic approach explores the representation of the female form within both Palestinian-Muslim and Palestinian-Christian cultural frameworks. She links the policing of the Arab woman's sexuality directly to the perception of the body in Christian culture.

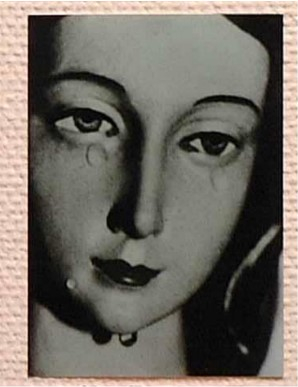

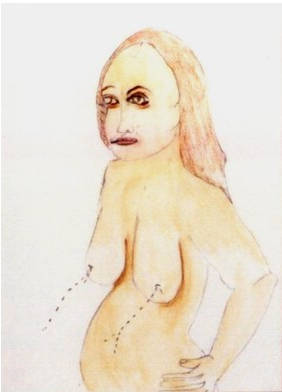

In a series of works titled “Sainthood and Sanity-hood” (2001), Abboud placed three works side by side: A postcard featuring a picture of Mary Magdalene with tears streaming down her face (fig. 1), a drawing of a naked woman whose breasts are dripping milk (fig. 2), and a drawing of a woman displaying her vagina (fig. 3).

Fig. 1. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, post card from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Fig. 2. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Fig. 3. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, post Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Regarding the use of the picture of Mary Magdalene in her instillation, one can give different interpretations. Mary Magdalene is one of the most important women in the Christian religion, and throughout history has been presented as a saint, condemned as a sinner, labeled as a prostitute, and even mentioned as the wife of Jesus. She was so devoted to Jesus that she even wiped his feet with her hair, as mentioned in the Gospels. In her use of this image, Abboud juxtaposes the sensuality emanating from the woman's form with the portrayal of Mary Magdalene as the saintly figure known for her repentance, as Tal Ben Zvi points out [Ben Zvi, 2004, p. 104].

Placing a postcard of Mary Magdalene next to drawings of women, one of whom squirts milk from her breasts and the other shows her genitals, according to Ben Zvi, functions as a kind of “warning sign” [Ben zvi, 2004, p. 105]. Mary Magdalene, with the symbolism she carries as a woman who has sinned, repented, and dedicated her life to Jesus, warns against such female behavior. This is not a feminist celebration of women taking pride in their genitals and proudly displaying them to the world, as can be seen in some Western feminist artworks that choose to emphasize the uniqueness of the female body, celebrate it, and see it as a means of expression and a tool for empowering femininity – something that is considered one of the main issues in the feminist discourse [Dekel, 2011, p. 25]. It is a memorial to something else, it memorializes oppression through exposure.

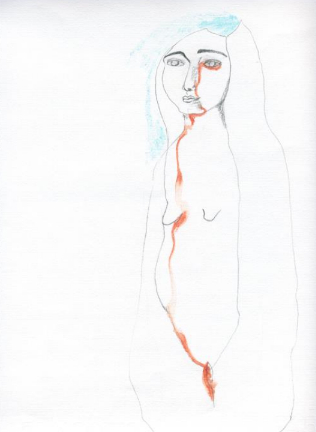

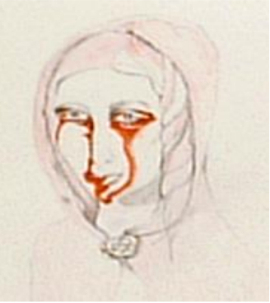

The artist uses the iconographic figures of additional female saints as a foundation for developing her own visual language in the same installation of “Sainthood and Sanity-hood.” The Virgin Mary, Saint Agatha, Saint Lucy, and Saint Eugenia clearly appear in the drawings based on popular Christian iconography. In all the drawings, the body is outlined and the flesh is only depicted as a white page. The Virgin is portrayed as a woman offering her red heart (fig. 4), a woman with flames on her head and exposed breasts being struck with arrows (fig. 5), symbolizing Saint Agatha; a female figure with a halo above her head and marking her genitals (fig. 6), linked to the story of Eugenia. Additionally, two drawings (fig 7-8) depict a woman with tears of blood flowing from her eyes, representing Saint Lucy, whose eyes, as per folk tradition, were cruelly gouged out in the name of sanctifying the Christian religion.

Fig. 4. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Fig. 5. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Fig. 6. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Fig. 7. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Fig. 8. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Ben Zvi points out that these works are connected to the concept of the “Lust of the Flesh” in Christian theology [Ben Zvi, 2004, p. 106]. Lust of the flesh, one of the most serious of the seven sins, was traditionally associated with women, and the punishment for it was directed toward the parts of the body involved in the sinful act. The lust for the flesh is depicted in the works mentioned as causing physical harm to the female body, foreshadowing violence to come. According to Abboud, sexuality is policed through fear and the threat of injury and death. In these works, the artist draws a parallel between honor killings, typically associated with Arab society, and expands the concept to include terrorism against women's sexuality [Ben Zvi, 2004, p. 107].

Abboud admits that she is discontented with the fact that since she was young, growing up in a Catholic family, she was taught to admire “good women” such as her own devoted mother and the pious Mary. However, she is also infuriated by the idea of the oppression to which women are subjected. Abboud’s art questions the concepts of holiness and sacrifice, highlighting the gap between women's individuality and their expected social roles. She places the sexual body at the center of her work and it is seen as a field of political action, and as a source of protest and self-observation. The works of the installation explore the female body as a metaphor, reflecting personal experiences and various social phenomena that demonstrate her ambiguous connection with Arab Christian womanhood [Ankori, 2006, p. 388].

Holy men

Although Fatima Abu Rumi (b. 1977) primarily incorporates symbols from the Muslim world into her art, Christian symbols can also be found in her work. Born in Tamra in the Lower Galilee, Abu Rumi often addresses the status of women in Arab society. One of Abu Rumi's notable characteristics is her unconventional portrayal of subjects that convey a sense of restlessness through profound silence. An example of this is seen in her portraits of her father, wh ere she veils the lower part of his face. In the painting “Father and I” (2005) (fig. 9) a clear hierarchy is evident. The father's commanding presence, symbolizing male authority, occupies the foreground, while the female figure stands behind him. Abu Rumi herself is depicted covered fr om head to toe, with only her eyes unveiled, gazing directly at the viewer. Her father is shown in profile, dressed in a traditional yellow abaya (cloak), with a halo above his head. Although he has his back turned to the viewer, he remains attentive to the situation, sheltering Abu Rumi. The floor is decorated with blue arabesque patterns and a teddy bear positioned on the left side alludes to childhood. The scene is depicted in dark lighting, with the only source of illumination apparently coming from the father's yellow cloak.

Fig. 9. Abu Rumi, Fatima, Father and I, 2005, Oil paints and beads on canvas, 200x150 cm. The artist's collection.

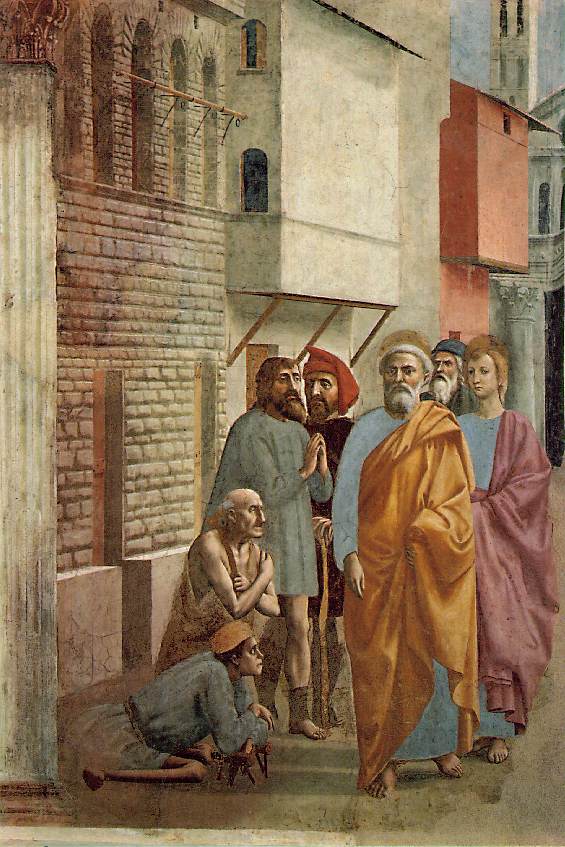

Looking closely at the figure of the father in the work, it seems that there is an influence from a painting of Masaccio’s dating back to 1426-27, titled “Saint Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow” (fig. 10). The scene depicts the divine ability of Saint Peter to heal the sick with the help of his shadow. At first glance, it was possible to notice a certain similarity between the figure of the father in Abu Rumi's contemporary painting and the figure of Saint Peter in Masaccio’s painting. The figure of the father in Abu Rumi's painting is depicted in a yellow garment, a color often associated with the figure of St. Peter in Renaissance paintings, which is also depicted in Masaccio’s work, with a halo hovering above the father's head, hinting at a sense of sanctity and divine connection. However, in a conversation with the artist about the possibility of such an influence, she stated that she did not know Masaccio’s painting at all [Abu Rumi, personal communication, April 22, 2024]. According to her, the father's figure is indeed similar to the figure of St. Peter, but this is merely a coincidence. In that conversation, the artist explained her intentions and why she chose to give the father figure an attribute from the world of Christianity. “I'm talking about patriarchal power wh ere the man has clear control, to such a level that the father, brother, husband, or any other male in a woman's life can interfere in her personal affairs” [Abu Rumi, personal communication, April 22, 2024]. Abu Rumi emphasized that this is what she believed twenty years ago. According to her, this belief is less prevalent today. The father in the artist's painting does not specifically refer to the figure of her own father but represents everything in the life of a woman living in a society that discredits women and allows men to take control. Just as the figure of the father in the painting dominates the space and almost obscures the female figure, it symbolizes how men can take over a woman's life in such a society. At the same time, her choice to give an aura to the male figure in the painting, according to her, refers to the sanctity of that male figure whose authority cannot be challenged. She points out that despite her father’s control and takeover of her life, he is considered a saint to be respected.

Fig. 10. Masaccio, St Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow, 1426-27, Fresco, 230x162 cm, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

Despite the lack of intertextuality with Masaccio’s painting of St. Peter healing with the help of his shadow, the comparison of the father figure to St. Peter in terms of interpretation of the painting remains the same. Just as Abu Rumi, both in the painting and in her life, lived under the “shadow” of the father, who symbolizes all male figures in her life, the sick man in Masaccio’s painting is similarly depicted under Peter's shadow. It is only within that shadow that healing by the sanctity of St. Peter can occur. Like Abu Rumi, who lived under and critiqued that shadow, she also demonstrates respect and finds healing within it.

In another installation by artist Abu Rumi, she continues to incorporate Christian symbolism to express criticism of male dominance. In her installation “My Mother's Braid” (2009) (fig. 11), the artist creates a crown of thorns with her own hands and entwines it with hair. During a conversation with the artist, she states that the reference was to the crown of thorns that was forcibly placed on Jesus's head during the events before his crucifixion, and the hair is the real hair of her mother who kept it for a long time until she decided to use it in the installation. “My mother had very long hair, and she always dreamed of cutting it. However, my father prevented her fr om doing so, and for years there were discussions about this issue. Before she married my father, her brothers also prevented her from cutting her long hair,” the artist points out, “until one day, without asking my father, she took the scissors and cut her braid right from the neck” [Abu Rumi, personal communication, April 22, 2024]. Abu Rumi goes on to state that for her, the crown of thorns in her instillation is seen as something masculine, while the hair represents the feminine. She combines these elements in her artwork and creates a new meaning. Additionally, the artist points out that the crown symbolizes anguish and pain. Various symbolic aspects are referred to by the artist. Abu Rumi uses her mother's hair, which symbolizes the woman's dependence on men for decision-making. However, behind that hair there is a story, it is a story of resistance to patriarchal control. By cutting it, the mother expresses her rebellion against her husband and her brothers. The hair of her mother symbolizes oppression and rebellion at the same time, as it envelops the crown of thorns worn by Jesus, symbolizing his suffering. This suggests that regardless of a woman's choice – whether to rebel or conform– she is destined to endure pain. Moreover, in Arab culture, hair symbolizes feminine beauty, as reflected in the saying “a woman's crown is her hair”2. The artist's father, representing the patriarchal society, prohibited her mother from cutting her long hair, which was vital for her beauty. The comparison is drawn between this living crown of beauty and the crown of thorns worn by Jesus, highlighting the societal expectations imposed on women within a patriarchal structure. The same proverb “a woman's crown is her hair” will be interpreted in this installation as something tormenting, full of thorns that oppress the woman from moving forward, especially when considering Abu Rumi's statement that the crown of thorns represents the man and the hair represents the woman.

Fig. 11. Abu-Rumi, Fatima, My Mother's Braid, 2009, a branch of thorns and hair, 55x22 cm. The artist's collection.

Abu Rumi's choice of documenting personal stories in her art to express criticism is one of the characteristics of the first generation of feminists’ art in the West. It is a postmodern principle that collapses the boundaries between the private and the public. Many feminist artists created art with a personal tone and chose to tell personal stories from their everyday lives to convey the message that “the personal is political” [Dekel, 2011, p. 167].

Madonna's cry

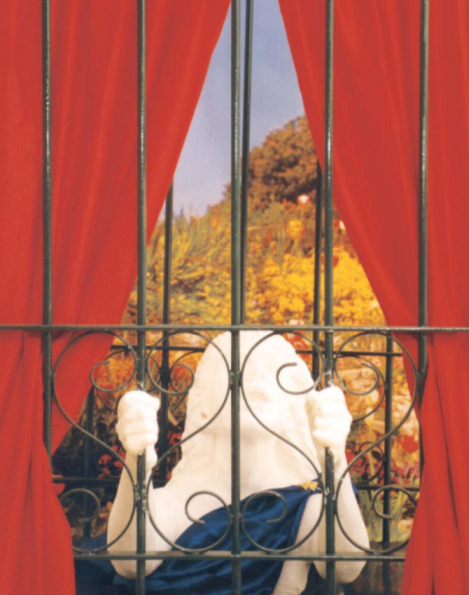

Another artist whose works are dominated by Christian symbols is Faten Nastas Mitwasi (b.1975), who was born in the city of Bethlehem. In her work “Woman in the Window” (2000) (fig. 12), she positions a plaster statue of a woman between two iron windows. The woman is depicted holding onto the bars of the front window, appearing to shout. In the background, behind the bars of the second window, hangs a picture of a Palestinian landscape. A red satin curtain drapes over one window, and a blue satin scarf is arranged diagonally across the woman's shoulders, fastened with a golden pin of a horse. The artist's selection of colors aligns with the imagery typically associated with the Virgin Mary in Christian iconography.

Fig. 12. Nastas Mitwasi, Faten, Woman in the Window, 2000, an image of the instillation (plaster, iron photograph), 150x60 cm. “Self Portrait- Palestinian women’s Art” Exhibition.

In this piece, The Virgin is situated between two windows that do not offer any means of escape. On one side, there is the rear window supposedly revealing a Palestinian landscape, yet it is merely a picture and not a real view. On the opposite side, the other window opens to the space wh ere viewers are positioned, allowing them to witness the woman's expression of distress. The space itself does not offer any refuge, exposing the figure to the scrutiny of all onlookers. Nastas places the woman within a domestic setting that is traditionally considered private, overlapping with the public realm, thereby blurring the boundaries between the two. However, the same woman who is under the eyes of society, which we, the observers fr om the front window, supposedly represent, is still between iron pillars that express the claustrophobia of a person under a suffocating occupation.

The woman is subjected to surveillance, visible from both the rear and front windows. Despite being depicted as imprisoned, the artist conveys that she emerges victorious – symbolizing an iconography of triumph (Ben Zvi, 2001, p. 98). By incorporating the image of Mary, Nastas intensifies the sense of victory portrayed in the artwork. This significant female figure has the ability to represent all women, embodying strength and resilience.

The other good shepherd

Born in Sha'ab in the Lower Galilee, Samah Shihadi (b. 1987) is another artist who embraces religious symbolism in her art. Shihadi's works are interwoven with religious, ritual, political, and cultural symbolism, which require the viewer to decipher them in order to absorb deeper meanings. Shihadi paints in a figurative style, using pencil, charcoal, and oil. Her artworks depict the power dynamics within the family, showcasing the relationships between men and women within a patriarchal society. In her art, Shihadi delves into the female experience and the struggles that women face in her society. Her works extends to women worldwide who encounter discrimination, marginalization, identity crises, and various gender-related challenges. The artist incorporates the dramatic flair of hyper realistic drawing through the Chiaroscuro technique, immersing the viewer in a fictional world. In her paintings, the artist's critique is expressed through portraying women from a standpoint of strength rather than the other way around. An example of this can be seen in a series of artworks wh ere the artist is depicted as a figure of high status and authority. In one particular painting titled “Saint” (2020) (fig. 13) it is strikingly evident how the artist draws parallels between herself and figures like Mary or Jesus, drawing inspiration fr om descriptions of the “ascension” scene from religious narratives (fig. 14). This portrait exudes a serene yet powerful aura, with the artist seemingly transcending earthly constraints as she floats, surrounded by a divine presence.

Fig. 13. Shihadi, Samah, Saint, 2020, charcoal on paper.

Fig. 14. Rembrandt, van Rijn, The Ascension of Christ,1636, Oil on canvas, 93x69 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

In another painting named “Rebirth” (2022) (fig. 15), the artist incorporates a fig leaf, which holds high symbolism in Christian art. As mentioned in the book of Genesis, the fig leaf was used by Adam and Eve to cover their nudity after eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge. The concept of the fig leaf is borrowed to signify the act of disguising or concealing actions, typically associated with a negative connotation. In this self-portrait, the artist depicts a very suggestive scene, “crowning” her face with fig leaves. Her direct gaze towards the viewer suggests a message of defiance, as if daring the audience to attempt to obscure her essence. The symbolism of fig leaves in this context holds a crucial significance, as the intentional exposure of the woman's face represents a display of strength and empowerment. There might be also a reference here to the concept of “concealment”. The use of the fig leaf as a symbol to hide or disguise certain actions, often with a negative connotation, alludes to the notion of concealment within Arab society. In a patriarchal societal structure, a “good woman” is often seen as one who does not draw attention to herself, remaining silenced. Furthermore, there exists a tradition of suppressing and concealing acts deemed taboo. In this painting, the abundance of symbolism arises from the woman's ability to have her face “seen” and “heard” despite the efforts of the fig leaves to conceal it.

Fig. 15. Shihadi, Samah, Rebirth, 2022, Charcoal on paper, 70x70 cm.

In another painting, the artist depicts a woman caressing a lamb and gives the painting the title “The Good Shepherd” (2020) (fig. 16). The concept of the good shepherd serves as a biblical allegory for God in Christianity, representing Jesus Christ. This allegory likens God or Jesus to a shepherd who lovingly tends to his flock, with the sheep symbolizing people or humanity in general. The artist's exhibition website states that the piece refers to a Middle Eastern saying that suggests a man who communicates openly with a woman in an equal dialogue is weak, like a sheep that follows the flock [Calò, 2020]. The idea that she replaces the figure of Jesus with a female figure expresses a clear feminist position. It conveys a message of empowerment as the flock follows and listens to a female figure rather than a male one.

Fig. 16. Shihadi, Samah, The Good Shepherd, 2020, Charcoal on paper.

Conclusion

This article analyzed the works of four Palestinian artists who choose to criticize the patriarchal society they come from. These four artists come from different backgrounds and reside in different areas of historical Palestine. This diversity warrants further research to comprehend how their backgrounds impact their artistic production. The application of a feminist lens to analyze their use of Christian symbols and compositions in their art provides insights and conclusions concerning their “quoting”. As mentioned earlier, it is interesting to grasp the reasoning behind quoting from iconography that predominantly presents the masculine perspective and not quoting feminine deities as Western feminist artists usually do. Upon scrutinizing the works of these artists, it becomes apparent that their use of these symbols primarily disrupts traditional power structures and challenges dominant narratives that promote male dominance, evident in the works of Shihadi and Abu Rumi. Shihadi eschews clear figures from the Christian realm but instead embraces Christian allegories, compositions, and symbols, infusing them into scenes that imbue them with fresh significance. The artist's critique is somewhat obscure, with more of a desire to transport the viewer to a celestial realm wh ere women hold considerable influence. Conversely, Abu Rumi narrates her own story as well as that of every woman in a patriarchal society. Abu Rumi does not showcase the strength of women who, despite adversities, triumph over their struggles, but rather the harsh reality and even the vulnerability of women who often linger in the shadows of men. By deploying Christian symbols and symbolism, the artist can narrate stories fr om multiple perspectives, all stemming from a common source – a society that often reveres men. These two artists engage in reclaiming and reinterpreting symbols that served historically to perpetuate patriarchal values. Additionally, the artists analyzed in this article harness these symbols to underscore the intersections of gender, religion, and culture in their society, as Abboud demonstrates in her works. Through employing figures of saints she revered as a girl, Abboud condemns the surveillance and policing of women and their sexuality. The artist's critique is manifest in her use of figures representing the same saints who sacrificed their lives and, to some extent, their sexuality for a male figure, Jesus. Lastly, the use of symbols from the Christian world can be linked to their universality and familiarity. This aspect serves as a compelling rationale for all four artists. In order to assert their criticism effectively, they utilize symbols and figures that are near universal, as seen in Nastas's incorporation of the figure of the Virgin Mary in her installation. Nastas uses the image of the Virgin Mary, symbolizing all women in her work. The artist employs a saintly figure representing women who, despite facing numerous challenges, emerge triumphant. Her cry is not one of agony or despair, but a declaration of victory and heroism.

SOURCES

1. Abu Rumi F. Personal communication with Fatima Abu Rumi (interview). 2024.

2. Ben Zvi T. Between nation and gender: the representation of the female body in Palestinian art: Master’s. Tel Aviv-Yafo, Tel Aviv University, 2004.

3. Ben Zvi T. “Self Portrait: Palestinian Women’s Art.” Self Portrait- Palestinian Women’s Art. Exhibition catalogue. Tel Aviv, Andalus Publishing, 2001. P. 148-158.

4. Calo E. TERRA (UN)FIRMA. 2020 Available at: https://www.tabariartspace.com/exhibitions/59-terra-un-firma-online-samah-shihadi/press_release_text... (accessed: 24.04.2024).

REFERENCES

1. Ankori G. “Re‐Visioning Faith: Christian and Muslim Allusions in Recent Palestinian Art.” Third Text. 2006. No.3-4(20). P. 379-390.

2. Dekel T. (M)Mwgdarwt: ʾomanwt whagwt pemiyniysṭiyt. Qaw ʾadwm - ʾOmanwt. Tel-Aviv: hakibyts hameaohad, 2011. (in Hebrew)

3. Heydemann N. “The Art of Quotation. Forms and Themes of the Art Quote, 1990-2010. An Essay.” The Art of Reception, edited by Jacobus Bracker and Ann-Kathrin Hubrich. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2021. P. 8-50.

4. Korte A. “Madonna’s Crucifixion and the Woman’s Body in Feminist Theology.” Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture, edited by Rosemarie Buikema and Iris van der Tuin, 1st ed. New York, Routledge. 2009. P. 117-134.

ИСТОЧНИКИ

1. Abu Rumi F. Personal communication with Fatima Abu Rumi (interview). 2024.

2. Ben Zvi T. Between nation and gender: the representation of the female body in Palestinian art: Master’s. – Tel Aviv-Yafo: Tel Aviv University, 2004.

3. Ben Zvi T. Self Portrait: Palestinian Women’s Art // Self Portrait- Palestinian Women’s Art. Exhibition catalogue. – Tel Aviv: Andalus Publishing, 2001. – P. 148-158.

4. Calo E. TERRA (UN)FIRMA. 2020. Режим доступа: https://www.tabariartspace.com/exhibitions/59-terra-un-firma-online-samah-shihadi/press_release_text... (дата обращения: 24.04.2024).

ЛИТЕРАТУРА

1. Ankori G. Re‐Visioning Faith: Christian and Muslim Allusions in Recent Palestinian Art // Third Text. 2006. No.3-4(20). P. 379-390.

2. Dekel T. (M)Mwgdarwt: ʾomanwt whagwt pemiyniysṭiyt. Qaw ʾadwm – ʾOmanwt. – Tel-Aviv: hakibyts hameaohad, 2011.

3. Heydemann N. The Art of Quotation. Forms and Themes of the Art Quote, 1990-2010. An Essay. // The Art of Reception. Edited by Jacobus Bracker and Ann-Kathrin Hubrich. – Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2021. – P. 8-50.

4. Korte A. Madonna’s Crucifixion and the Woman’s Body in Feminist Theology // Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture. Edited by Rosemarie Buikema and Iris van der Tuin, 1st ed. – New York: Routledge. 2009. – P. 117-134.

LIST OF ILUSTRATIONS

Figure 1. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, post card from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Source: https://www.hagar-gallery.com/hagswf/exhibitions/JumanaEmilAboud.pdf

Figure 2. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Source: https://www.hagar-gallery.com/hagswf/exhibitions/JumanaEmilAboud.pdf

Figure 3. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, post Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Source: https://www.hagar-gallery.com/hagswf/exhibitions/JumanaEmilAboud.pdf

Figure 4. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Source: https://www.hagar-gallery.com/hagswf/exhibitions/JumanaEmilAboud.pdf

Figure 5. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Source: https://www.hagar-gallery.com/haghtml/ju11aM.htm

Figure 6. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Source: https://www.hagar-gallery.com/hagswf/exhibitions/JumanaEmilAboud.pdf

Figure 7. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Source: https://www.hagar-gallery.com/hagswf/exhibitions/JumanaEmilAboud.pdf

Figure 8. Emil Abboud, Jumana, Sainthood and Sanity-hood, 2001, Drawing from the instillation, Hagar Art Gallery, Israel.

Source: https://www.hagar-gallery.com/hagswf/exhibitions/JumanaEmilAboud.pdf

Figure 9. Abu Rumi, Fatima, Father and I, 2005, Oil paints and beads on canvas, 200x150 cm. The artist's collection.

Source: https://museum.imj.org.il/artcenter/includes/itemH.asp?id=650379

Figure 10. Masaccio, St Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow, 1426-27, Fresco, 230x162 cm, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

Source: https://www.wga.hu/html_m/m/masaccio/brancacc/st_peter/shadow.html

Figure 11. Abu-Rumi, Fatima, My Mother's Braid, 2009, a branch of thorns and hair, 55x22 cm. The artist's collection.

Figure 12. Nastas Mitwasi, Faten, Woman in the Window, 2000, an image of the instillation (plaster, iron photograph), 150x60 cm.

Source: caption from the exhibition catalogue “Self Portrait- Palestinian women’s Art”, p.100.

Figure 13. Shihadi, Samah, Saint, 2020, charcoal on paper.

Source: https://cromwellplace.com/membership/tabari-artspace

Figure 14. Rembrandt, van Rijn, The Ascension of Christ, 1636, Oil on canvas, 93x69 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

Figure 15. Shihadi, Samah, Rebirth, 2022, Charcoal on paper, 70x70 cm.

Source: https://www.artsy.net/artwork/samah-shihadi-rebirth-1

Figure 16. Shihadi, Samah, The Good Shepherd, 2020.

Source: https://www.tabariartspace.com/exhibitions/63/works/artworks1561/

СНОСКИ

1 “Nakba” (Arabic: النكبة) is a term that translates to “catastrophe” and refers to the tragic events experienced by the Palestinian people on their land, wh ere half of the population was expelled from their homes by the Zionists, becoming refugees with no right of return to their homeland. Thousands of individuals were killed and numerous villages were destroyed during these events.

2 “taj almara shaa’rha” (Arabic: تاج المرأة شعرها).

About us

- Our history

- Editorial council and editorial board

- Authors

- Ethical principles

- Legal information

- Contacts

To our authors

- Regulations for the submission and consideration of articles

- Publication ethics

- Academical formalisation

- Malpractice statement

Issues

- Issue 58 (2025, 2)

- Issue 57 (2025, 1)

- Issue 56 (2024, 4)

- Issue 55 (2024, 3)

- Issue 54 (2024, 2)

- Issue 53 (2024, 1)

- Issue 52 (2023, 4)

- Issue 51 (2023, 3)

- Issue 50 (2023, 2)

- Issue 49 (2023, 1)

- Issue 48 (2022, 4)

- Issue 47 (2022, 3)

- Issue 46 (2022, 2)

- Issue 45 (2022, 1)

- Issue 44 (2021, 4)

- Issue 43 (2021, 3)

- Issue 42 (2021, 2)

- Issue 41 (2021, 1)

- Issue 40 (2020, 4)

- Issue 39 (2020, 3)

- Issue 38 (2020, 2)

- Issue 37 (2020, 1)

- Issue 36 (2019, 4)

- Issue 35 (2019, 3)

- Issue 34 (2019, 2)

- Issue 33 (2019, 1)

- Issue 32 (2018, 4)

- Issue 31 (2018, 3)

- Issue 30 (2018, 2)

- Issue 29 (2018, 1)

- Issue 28 (2017, 4)

- Issue 27 (2017, 3)

- Issue 26 (2017, 2)

- Issue 25 (2017, 1)

- Issue 24 (2016, 4)

- Issue 23 (2016, 3)

- Issue 22 (2016, 2)

- Issue 21 (2016, 1)

- Issue 20 (2015, 4)

- Issue 19 (2015, 3)

- Issue 18 (2015, 2)

- Issue 17 (2015, 1)

- Issue 16 (2014, 4)

- Issue 15 (2014, 3)

- Issue 14 (2014, 2)

- Issue 13 (2014, 1)

- Issue 12 (2013, 4)

- Issue 11 (2013, 3)

- Issue 10 (2013, 2)

- Issue 9 (2013, 1)

- Issue 8 (2012, 4)

- Issue 7 (2012, 3)

- Issue 6 (2012, 2)

- Issue 5 (2012, 1)

- Issue 4 (2011, 4)

- Issue 3 (2011, 3)

- Issue 2 (2011, 2)

- Issue 1 (2011, 1)

- Retracted articles

.png)