M. MADLEN The development of Christian iconography in Palestinian art: transitioning from religious imagery to secular representations of loss and memory after the Nakba

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY IN PALESTINIAN ART: TRANSITIONING FR OM RELIGIOUS IMAGERY TO SECULAR REPRESENTATIONS OF LOSS AND MEMORY AFTER THE NAKBA

Research article

UDC 7.036+75.045

DOI: 10.28995/2227-6165-2025-3-44-52

Received: May 20, 2025. Approved after reviewing: September 13, 202?. Date of publication: October 25, 2025.

Author: Madlen Mahameed, 2nd year PhD student, St. Petersburg State University of Culture, Department of Art History (Saint Petersburg, Russia), e-mail: madlen.m31@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0009-0002-3925-0771

Summary: This article explores the development of icon and religious painting in early 20th-century Palestine, focusing on how local artists adapted Christian iconography through a hybrid approach that blended Arab cultural expression with Western artistic influences. It traces the shift from traditional religious imagery to secular interpretations, especially after the Nakba, when artists repurposed Christian symbols – such as the crucifixion and resurrection – to address themes of national identity, memory, loss, and resistance. The article highlights how this visual language persisted among later generations, including female artists who use Christian imagery to explore personal and feminist narratives. By examining the continuity and transformation of iconographic language, the article offers insight into the evolving role of Christian symbols in Palestinian visual culture.

Keywords: Palestinian art, Christian iconography, 20th century art, Nakba, Hybridity

РАЗВИТИЕ ХРИСТИАНСКОЙ ИКОНОГРАФИИ В ПАЛЕСТИНСКОМ ИСКУССТВЕ: ПЕРЕХОД ОТ РЕЛИГИОЗНЫХ ОБРАЗОВ К СЕКУЛЯРНЫМ ПРЕДСТАВЛЕНИЯМ УТРАТЫ И ПАМЯТИ ПОСЛЕ НАКБЫ

Научная статья

УДК 7.036+75.045

DOI: 10.28995/2227-6165-2025-3-44-52

Дата поступления: 20.05.2025. Дата одобрения после рецензирования: 13.09.2025. Дата публикации: 25.10.2025.

Автор: Мадлин Махамид, аспирант 2 курса, Санкт-Петербургский государственный институт культуры, кафедра искусствоведения (Санкт-Петербург, Россия) e-mail: madlen.m31@gmail.com

ORCID ID: 0009-0002-3925-0771

Аннотация: В данной статье рассматривается развитие иконописи и религиозной живописи в Палестине начала XX века, с акцентом на то, как местные художники адаптировали христианскую иконографию с помощью гибридного подхода, сочетающего арабское культурное выражение с западными художественными влияниями. Прослеживается переход от традиционной религиозной образности к светским интерпретациям, особенно после Накбы, когда художники переосмыслили христианские символы – такие как распятие и воскресение – для выражения тем национальной идентичности, памяти, утраты и сопротивления. В статье подчеркивается, как этот визуальный язык сохранялся у последующих поколений, включая женщин-художниц, использующих христианскую образность для исследования личных и феминистских тем. Изучая преемственность и трансформацию иконографического языка, статья предлагает понимание меняющейся роли христианских символов в палестинской визуальной культуре.

Ключевые слова: палестинское искусство, христианская иконография, искусство ХХ века, Накба, гибридность

For citation:

Madlen M. “The development of Christian iconography in Palestinian art: transitioning from religious imagery to secular representations of loss and memory after the Nakba.” Articult. 2025, no. 3(59), pp. 44-52. (in Russian) DOI: 10.28995/2227-6165-2025-3-44-52

Christian symbolism and themes are being included into the works of various Palestinian artists. It is essential to recognize that the themes employed and the narratives derived from the New Testament have transcended their initial religious relevance. These aspects are being recontextualized to tackle contemporary political, social, and cultural challenges rather than fulfilling religious functions. This tactic reflects a similar technique utilized by Western artists who, by referencing Christian images, connect with a profound heritage. By doing so, they also cleanse these symbols of their original religious significances, creating a new discourse that departs from traditional interpretations, as noted by Alena Alexandrova [Alexandrova, 2017, p. 41].

Prior to the application of Christian iconography in a secular context, the initial history of image-making in Palestine was icon painting. A group of icon painters adhering to the Byzantine tradition operated in Jerusalem, however they differentiated themselves by a unique style, earning the designation “Jerusalem School.” According to Kamal Boullata, Jerusalem iconographical language is defined by the relocation of the church icon from its revered ecclesiastical setting to the language of “simplified popular art” [Boullata, 2000, p. 45]. Jerusalem icons exhibit a reduced number of figures relative to other regional artworks, resulting in more simplistic compositions. Local artists depicted figures with almond-shaped eyes and pronounced black contours, employing bright colors (fig. 1). Nisa Ari noted that they frequently depicted a genuine blue sky, occasionally even clouds, rather than the conventional golden backdrops [Ari, 2017, p. 68]. The existence of Arabic inscriptions along with a reduction in Greek inscriptions indicates the emergence of a unique painting style in Palestine. Boullata contends that this “Arabization” of icons signified a transition towards independence from Greek ecclesiastical authority [Boullata, 2009, p. 45].

Fig. 1. Muhanna al-Qudsi, Mikhail, The Virgin Mary, 1882, Icon detail, 51x42cm, Saint Tekla Convent, Ma’lula.

The emergence of a distinctive secular visual language in Palestine was profoundly shaped by the cultural diversity in Jerusalem and the global expansion of the Christian mission. The advent of photography and the exchanges between local icon painters and novel artistic mediums, tools, and creations by Orientalist and religious artists significantly impacted this evolution [Boullata, 2009, p. 46]. During this period, Palestinian society saw a diverse array of religious iconography and art originating from several movements based in Jerusalem. Boullata specifically emphasizes that local icon painters and the revival of secular Palestinian painting were predominantly influenced by Russian artists [Boullata, 2009, p. 47].

Nicola Saig (1863–1942), an essential Palestinian artist, profoundly impacted subsequent generations of painters and marked a significant transition from religious to secular painting. Saig's painting “Nativity scene” (c. 1920) (fig. 2) is often regarded by scholars as a pivotal work in the evolution of contemporary art in Palestine during the early 20th century.

Fig. 2. Saig, Nicola, Nativity Scene, c.1920, Oil on canvas, 35x64 cm, Khalid Shoman Foundation, Amman.

The “Nativity scene” is likely derived or largely copied from a replica of a late sixteenth-century European painting [Boullata, 2009, p. 109]. This artwork adeptly synthesizes Eastern and Western artistic influences by merging traditional and modern forms with both religious and secular elements. The artist has preserved the primary components of the triangle composition from its European origin, wherein the figures of Joseph, Mary, and the kneeling shepherd wear garments usually seen as characteristic of the biblical era. The artist concurrently incorporates further figures, potentially derived from imagination or photographs, including a Palestinian woman entering the cave and a young child alongside her wearing a tarbush common in the Ottoman times. The artist combines several occurrences into a unified composition: on the left, the Palestinian woman signifies the present, whereas on the right, the Nativity scene reflects the past [Boullata, 2009, p. 110].

Zulfa Al-Sa'di (1905-1988), Saig's student, was another key figure in the development of secular modern art in Palestine. She refers to Qudsi (Jerusalemite) Christian iconographic traditions through her formal methodology and the blending of word and picture. Al-Sa'di's works portray historical heroic figures, seemingly replicating pictures from that era. Similar to Byzantine iconography, she engraved the names of the figures represented in her paintings. Researcher Faten Nastas Mitwasi asserts that Al-Sa'di's images effectively conveyed explicit national and Arab sentiments while simultaneously articulating a potent anti-colonial political message that resonated profoundly across society [Nastas Mitwasi, 2015, p. 19]. Artist Daoud Zalatimo (1906-2001) also portrayed famous Arab figures from Islamic history, including Saladin (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Zalatimo, Daoud, Saladin, First half of the 20th century, Oil painting, 50x70cm.

The reason Zalatimo chose such significant figures from Islamic history is obvious: he wanted to establish a connection with the people and spread messages of rebellion that were relevant to the Palestinians' circumstances at the time, which included the British Mandate and the growing number of Zionist immigrants in the Land of Palestine. Boullata observes that Zalatimo's allegorical technique significantly contributed to the development of a national Palestinian iconography in post-Nakba art. This impact is seen in his student Ismail Shammout, who employed visual allegories in his artwork to convey concepts of memory and loss during the Nakba [Boullata, 2009, p. 67].

The catastrophic occurrences of the Nakba1 in 1948 interrupted the emergence of a secular creative legacy in the early 20th century. Luisa Gandolfo asserts that paintings created post-1948 emphasize themes of resistance, tragedy, loss, and remembering, in contrast to those produced prior to 1948, which predominantly showcased serene landscapes and religious motifs [Gandolfo, 2010, p. 48]. The inaugural generation of Palestinian artists post-1948 examined memory, depicting historical moments that influenced their experience of exile, unlike earlier generations who created narrative scenes that symbolically addressed historical events under British colonial rule [Boullata, 2009, p. 108].

In Palestinian art, 1948 signifies a pivotal year that marks a significant shift in its creation, distribution, and subject matter. The Nakba serves as the crucial historical event that shaped Palestinian art and the development of a unique regional visual language, forming the essential basis of the Palestinian community's collective memory. For years, themes of tragedy, grief, and suffering have remained pertinent and profoundly impacted the expressions of cultural leaders, serving as a foundational cornerstone for Palestinians since the emergence of its artistic representations in the 1950s. The artistic manifestations of Palestinian artists were influenced by the collective tragedy experienced in the wake of the Nakba, rather than by their individual emotions. Frantz Fanon posits that the quest for cultural and national self-identification often leads to a diminishment of individualism, revealing the collective identity of the community [Fanon, 1963, p. 47]. Following the Nakba, this phenomenon was particularly evident among Palestinian artists.

Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon assert that Boullata's claim indicates that art created in proximity to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is generally more symbolic in terms of style. On the other hand, art created in periods farther away from these occurrences tends to be more abstract. The need for spectators to understand the political and narrative implications ingrained in the artworks is perhaps the reason for this change [Makhoul and Hon, 2020, p.213]. While the abstract pieces encourage deeper reflection and individual interpretation, the conflict-driven art's strong symbolism enables instantaneous involvement with urgent issues and emphasizes the intricate connection between art and the sociopolitical environment in which it is produced. The use of Christian iconography in Palestinian art after 1948 is a noteworthy way to express these shared experiences. This iconography, which was first incorporated into a religious framework, has now been reinterpreted and stripped of its original religious meanings, enabling the artists to portray secular concepts that mirror the sociopolitical reality they encountered.

After 1948, the language of Palestinian imagery was characterized by gaps between the producers' languages and inconsistent artistic execution. One of the most significant commonalities across opposing creative concepts was the hybrid element. Gannit Ankori, an Israeli academic, highlights the importance of hybrid elements in Palestinian art, which are intimately related to the Palestinian people's history of displacement [Ankori, 2006, p. 22]. The term “third space,” coined by Homi Bhabha to describe a dynamic domain of interaction between the colonizer and the colonized, is used by Ankori in this context. This theoretical framework, which emphasizes the reciprocal influences that result from cultural collisions, is crucial to comprehending the “hybridity” found in Palestinian art.

Bhabha's theory posits that the interaction of multiple cultures generates a distinctive hybrid space, facilitating the formation of new cultural identities and manifestations that surpass their initial cultural contexts. This third sector in art provides a rich environment for exploration. Artists in postcolonial contexts derive inspiration from diverse sources, resulting in works that embody the intricate relationship between tradition and modern experience. This frequently leads to the emergence of novel forms and subjects that contest conventional creative limits [Bhabha, 1994, p. 6-54].

A considerable number of Palestinian artists explore issues of displacement, identity, and war, frequently utilizing a hybrid artistic methodology. In the aftermath of 1948, Palestinian art developed in multiple trajectories, both maintaining and differing from the artistic forms that preceded the Nakba. The central features of this evolution encompass cultural hybridization resulting from the amalgamation of Eastern and Western elements, a deliberate appropriation of local traditional religious artistic forms – including Arabic calligraphy, Islamic art, Christian icons, and folk embroidery – and an anti-colonialist iconography that expresses a collective Palestinian identity [Ankori, 2006, p. 47]. Hybridity is notably evident in Saig's artwork, particularly in his painting “Nativity scene,” as also noted by Boullata [Boullata , 2009, p.110], which exemplifies this idea. This artwork illustrates a nativity scene that, while influenced by European artistic traditions, combines unique Eastern elements, creating an unusual blend of styles. This mixture not only highlights Saig's heritage but also reflects the cultural interactions common throughout his day.

The hybridity of Palestinian art, evident in Saig's painting, persists from the earliest period following the Nakba, during which Palestinian artists began to include religious iconography in their works while simultaneously asserting nationalism. Ankori claims that these painters adeptly converted religious elements into national emblems, integrating them with the secular notion of national identity [Ankori, 2006, p. 380]. An illustrative instance of this phenomenon is the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which, as one of Islam's most sacred sites, emerged as a prominent and recurring motif in Palestinian art post-1967, aligning with the Israeli occupation of Jerusalem. Consequently, it became an emblem of the Palestinians' resistance to this occupation. The representation of the Dome of the Rock, the pivotal edifice emblematic of Palestinian identity in Jerusalem, is present in the works of nearly all recognized Palestinian artists, irrespective of their Muslim or Christian affiliation.

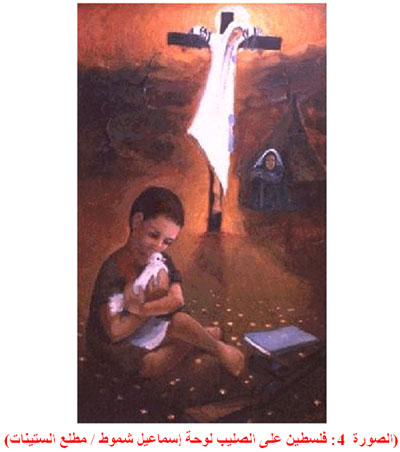

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Christian iconography influenced artists who created representations of the Palestinian refugee, embodying themes of suffering, purity, and sacrifice, derived from the rich Christian iconographic tradition. An illustration of this emerging style is Shammout's artwork “Palestine: A Land Crucified” (1958) (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Shammout, Ismail, Palestine: A Land Crucified, 1958.

This painting illustrates a towering cross, which, rather than a conventional crucifixion, showcases a figure attired in a kufiya and white robe, representing what seems to be a map of Palestine. The sun, positioned behind the head of the crucified “Palestine,” bestows upon it an unusual halo of sanctity. An older woman is seated at the entrance of a tent to the left of the cross, while a toddler in the foreground holds a white dove. At the feet of this Palestinian child rests a school backpack, books, and a gun, reflecting the dual aspects of the national struggle: the pen, signifying enlightenment, and the rifle, indicating armed resistance. Shammout articulated that this painting seeks to illustrate the three trajectories encountered by Palestinians: the diaspora and loss of homeland, symbolizing the Nakba as the past; the stark conditions endured in refugee camps, representing the present; and the hope for a future characterized by the pursuit of peace and happiness for children [Musilmani, 2022].

As previously stated, Shammout was influenced by the artist Zalatimo in his use of graphic allegories. Thus, Shammout's use of Christian iconography of the crucifixion to represent the Palestinian people's loss and grief may be linked to Zlatimo's use of figures from Muslim history to create an allegorical visual depiction of the Palestinian situation under British Mandate control.

Abd Abdi (b.1942), another post-Nakba artist who trained in East Germany, uses an image of the Messiah, who, as Maliha Musilmani describes, “is burdened by profound anguish and the oppressive weight of the reality of occupation” [Musilmani, 2022]. In the artist's painting “The Resurrection of Jesus,” (1973) a tall, bearded man walking barefoot and alone is depicted, with tents behind him (fig. 5). Jesus' “resurrection” is shown in a refugee camp, a reference to the resurrection of Palestinian refugees following the Nakba. The sorrow occurrence involving the Palestinians in the same land is linked by the artist to the religious event that occurred in Jerusalem.

Fig. 5. Abdi, Abed, The Resurrection of Jesus, 1973, Pen and ink on paper, included in the 1973 “Abed Abdi – Drawings” album.

Abdi, like many Palestinian painters in the first period after the Nakba, decided to express his emotions through Christian iconography. This serves to illustrate the association of the “Palestinian” Jesus with the land of Palestine, thereby highlighting the link between Palestinians and early Christianity, while also delivering national messages through a comprehensible visual lexicon, as Christian art left behind a wealth of imagery imbued with themes of hope, suffering, and sacrifice that resonate universally. Palestinian artists have articulated their suffering through the narrative of Jesus, characterized by sufferings and sorrow, creating images connected with Arabic poetry. Some artists have been influenced by Palestinian poets who derived their lyrical metaphors from the narrative of Jesus the Messiah [Boullata,2009, p. 206]. The theme of Jesus' passion has consistently inspired numerous Palestinian poets, irrespective of their theological backgrounds–Christian, Muslim, or Druze–whose native language features the terms fadi, meaning “savior,” and fidai, meaning “freedom fighter,” both derived from a same root [Boullata,2001, p. 76]. These Palestinian poets used analogies that allowed the agonies of Jesus to express their suffering in the same place wh ere Jesus was tortured and crucified. Jesus’ tragedy as a Palestinian, not only as a symbol but as an actual reality, is represented in the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish – a notable Palestinian national poet – as a personal experience when he was uprooted fr om his village, persecuted and found himself a refugee in his own land.

Ankori notes that emerging artists persist in integrating religious elements into their creations, however with greater individuality and complexity [Ankori, 2006, p. 390]. This is an art form characterized by personal dimensions and multiple layers of significance. According to Steve Sabella, In the 1990s, following the expansion of the Palestinian cultural landscape and the introduction of new artistic techniques, the artistic language transitioned from a collective, illustrated, figurative, and narrative symbolism to a more individual and personally expressive form [Sabella, 2010, p. 90]. The enhanced mobility in the 1990s afforded Palestinian artists the chance to transcend collective ambitions and pursue self-reflection and individual reflection.

At the same time, the practice of incorporating religious symbols persists among young female artists influenced by Western feminist rhetoric. As Ankori observes, these artists maintain a connection to their national, cultural, and religious heritage, although they do it “through a complex, critical feminist prism”[Ankori, 2006, p. 390]. For instance, Samah Shihadi (b. 1987) explores her identity and status as an Arab woman in a patriarchal society by using Christian symbols, like as crosses (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Shihadi, Samah, Lying Down, 2015, Pencil on paper, 151x207cm.

The artist explains that the cross evokes crucifixion, which includes the binding of hands and feet, leading to immobility, which mirrors the status of women in society broadly and in Arab society specifically. Women are always constrained. Someone is constantly in control of them [Shihadi, 2024].

Christian imagery and theological references have also been employed recently by other artists to draw attention to social issues, especially from a feminist standpoint. In this way, they add a layer of Christian imagery to Palestinian art that is very different from the painters of the preceding generation.

In conclusion, icon painting emerged as one of the earliest forms of visual representation in Palestine. Early 20th-century Palestinian icon painters integrated Western creative methods, receiving inspiration from various artists who traveled to Jerusalem globally, as a result secularizing the region's art. The concept of “hybridity” in Palestinian art was expressed by artists before the Nakba, who, in essence, “inhabited” a third space, influenced by diverse Western artistic styles and techniques. Nonetheless, despite this impact, Palestinian artists included elements pertinent to their identity and tradition, including the utilization of the Arabic language in icons and the representation of characters associated with their history. The incorporation of secular elements in religious-themed paintings by artists like Saig may have impacted post-Nakba artists who integrated religious motifs within a secular framework. Similarly, the incorporation of prominent figures from Arab history by numerous Palestinian artists in their works, intended to communicate anti-colonial messages, is a crucial element that may have also impacted post-Nakba artists who utilized the image of Christ as a significant figure in the history of Palestinian territory.

The political transformations of the early 20th century and the devastating occurrences of the Nakba in 1948 profoundly influenced the Palestinian art landscape, prompting artists to explore themes related to Arab history that elicit sentiments of pride and potential rebellion against the Western presence in the region, as well as themes of memory and loss following the Nakba. These experiences shaped their artistic expression, resulting in a transition from traditional iconographic works to expressionist and realistic paintings that embodied their collective identity. During the 1950s and early 1960s, artists began describing their Palestinian experience using Christian imagery, which was extricated from its religious setting and recycled to convey concepts pertinent to the prevailing circumstances in the region.

Artists like Shammout, likely influenced by Zalatimo, employed crucifixion iconography within a refugee camp, using a visual lexicon derived from Western imagery that promotes effective communication and message transmission, despite the “Palestinization” of the scenario. At the same time, the artist Abdi, who was influenced by western art traditions, depicted Jesus' resurrection among Palestinians at a refugee camp in order to represent the Palestinians' resurrection as connected to Jesus' resurrection in that area. Both artists exhibit a different “hybridity,” as they employ Western iconographic language infused with a Palestinian narrative. Despite the passage of time, younger Palestinian artists persist in employing Christian iconography to convey collective notions associated with Palestinian identity. Simultaneously, the artists' engagement with Western artistic influences prompts them to explore more personal topics, and over the years, numerous female artists choose to address feminist themes using Christian imagery. The evolution of topics that Palestinian artists depict through Christian iconography requires additional investigation, which could provide new understandings into this unique approach.

SOURCES

1. Musilmani M. Mariam walmaseeh fe alfan alfalastini..darb alalam almawaod fe alkhalas. Available at: https://diffah.alaraby.co.uk/diffah//arts/2022/1/7/%D9%85%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%85-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%AD-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B7%D9%8A%D9%86%D9%8A-%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A2%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B5 (accessed: 05.01.2024).

2. Shihadi S. Personal communication with Samah Shihadi.2024.

REFERENCES

1. Alexandrova A. Breaking resemblance: the role of religious motifs in contemporary art. New York, Fordham University Press, 2017.

2. Ankori G. Palestinian Art. London, Reaktion Books, 2013.

3. Ankori G. “Re‐Visioning Faith: Christian and Muslim Allusions in Recent Palestinian Art.” Third Text. 2006. Vol. 20. Re‐Visioning Faith. N 3-4. P. 379-390.

4. Ari N. “Spiritual capital and the copy: Painting, photography, and the production of the image in early twentieth-century Palestine.” Arab Studies Journal. 2017. Vol. 25. N 2. P. 60-99.

5. Bhabha H. K. The location of culture / H. K. Bhabha. – London ; New York : Routledge, 2004. – 408 p.

6. Boullata K. “’Asim Abu Shaqra: The Artist’s Eye and the Cactus Tree.” University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies. 2001. Vol. 30. N 4. P. 68-82

7. Boullata K. Istihdar al-makan: Dirasah fi al-fann al-tashkili al-Filastini al-muasir. Tunisia, almunazama alearabia liltarbia walthaqafa walfunun, 2000.

8. Boullata K. Palestinian art: 1850 to the Present. Palestinian art. London, Saqi, 2009.

9. Fanon F. The wretched of the earth. C. Farrington tran. . New York, Grove Press, 1963.

10. Gandolfo K.L. “Representations of Conflict: Images of War, Resistance, and Identity in Palestinian Art.” Radical History Review. 2010. Vol. 2010. N 106. P. 47-69.

11. Makhoul B., Hon G. Al-fann al-filastini al-muasir: al-usul, al-qawmiyya, al-hawiyya. A. Abu shrarah tran. . Beirut, Muʾassasat al-Dirasat al-Filastiniyya, 2020.

12. Natas Mitwasi F. Reflections on Palestinian Art Art of Resistance or Aesthetics. Beit Jala, Latin Patriarchate, 2015.

ИСТОЧНИКИ

1. Musilmani M. Mariam walmaseeh fe alfan alfalastini..darb alalam almawaod fe alkhalas. Режим доступа: https://diffah.alaraby.co.uk/diffah//arts/2022/1/7/%D9%85%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%85-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%AD-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B7%D9%8A%D9%86%D9%8A-%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A2%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B5 (дата обращения: 05.01.2024).

2. Shihadi S. Personal communication with Samah Shihadi. 2024.

ЛИТЕРАТУРА

1. Alexandrova A. Breaking resemblance: the role of religious motifs in contemporary art. – New York: Fordham University Press, 2017.

2. Ankori G. Palestinian Art. – London: Reaktion Books, 2013.

3. Ankori G. Re‐Visioning Faith: Christian and Muslim Allusions in Recent Palestinian Art // Third Text. 2006. Vol. 20. Re‐Visioning Faith. № 3-4. P. 379-390.

4. Ari N. Spiritual capital and the copy: Painting, photography, and the production of the image in early twentieth-century Palestine // Arab Studies Journal. 2017. Vol. 25. № 2. P. 60-99.

5. Bhabha H. K. The location of culture. – London; New York: Routledge, 2004.

6. Boullata K. ’Asim Abu Shaqra: The Artist’s Eye and the Cactus Tree // University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies. 2001. Vol. 30. № 4. P. 68-82

7. Boullata K. Istihdar al-makan: Dirasah fi al-fann al-tashkili al-Filastini al-muasir. – Tunisia: almunazama alearabia liltarbia walthaqafa walfunun, 2000.

8. Boullata K. Palestinian art: 1850 to the Present. Palestinian art. – London: Saqi, 2009.

9. Fanon F. The wretched of the earth / C. Farrington translate. – New York: Grove Press, 1963.

10. Gandolfo K.L. Representations of Conflict: Images of War, Resistance, and Identity in Palestinian Art // Radical History Review. 2010. Vol. 2010. № 106. P. 47-69.

11. Makhoul B., Hon G. Al-fann al-filastini al-muasir: al-usul, al-qawmiyya, al-hawiyya / A. Abu shrarah translate. – Beirut: Muʾassasat al-Dirasat al-Filastiniyya, 2020.

12. Natas Mitwasi F. Reflections on Palestinian Art Art of Resistance or Aesthetics. – Beit Jala: Latin Patriarchate, 2015.

LIST OF ILUSTRATIONS

Fig. 1. Muhanna al-Qudsi, Mikhail, The Virgin Mary, 1882, Icon detail, 51x42cm, Saint Tekla Convent, Ma’lula.

Source: “Palestinian art: 1850 to the Present”/ K. Boullata, 2009, p.44.

Fig. 2. Saig, Nicola, Nativity Scene, c.1920, Oil on canvas, 35x64 cm, Khalid Shoman Foundation, Amman.

Source: https://selectionsarts.com/george-al-ama-for-modern-art-and-artist-estates-ways-works-and-archives-issue/

Fig. 3. Zalatimo, Daoud, Saladin, First half of the 20th century, Oil painting, 50x70cm.

Source: “Istihdar al-makan: Dirasah fi al-fann al-tashkili al-Filastini al-muasir”/ K. Boullata, 2000, p. 40.

Fig. 4. Shammout, Ismail, Palestine: A Land Crucified, 1958.

Source: https://myportail.com/actualites-news-web-2-0.php?id=6025

Fig. 5. Abdi, Abed, The Resurrection of Jesus, 1973, Pen and ink on paper, included in the 1973 “Abed Abdi – Drawings” album.

Source: https://abedabdi.com/portfolio/the-resurrection-of-jesus/

Fig. 6. Shihadi, Samah, Lying Down, 2015, Pencil on paper, 151x207cm.

Source: https://www.donneearte.ch/virtual-museum/sonntag-17-mai-2020-samah-shihadi

FOOTNOTES

1 “Nakba” (Arabic: النكبة) is a term that translates to “catastrophe” and refers to the tragic events experienced by the Palestinian people on their land, wh ere half of the population was expelled from their homes by the Zionists, becoming refugees with no right of return to their homeland. Thousands of individuals were killed and numerous villages were destroyed during these events.

About us

- Our history

- Editorial council and editorial board

- Authors

- Ethical principles

- Legal information

- Contacts

To our authors

- Regulations for the submission and consideration of articles

- Publication ethics

- Academical formalisation

- Malpractice statement

Issues

- Issue 59 (2025, 3)

- Issue 58 (2025, 2)

- Issue 57 (2025, 1)

- Issue 56 (2024, 4)

- Issue 55 (2024, 3)

- Issue 54 (2024, 2)

- Issue 53 (2024, 1)

- Issue 52 (2023, 4)

- Issue 51 (2023, 3)

- Issue 50 (2023, 2)

- Issue 49 (2023, 1)

- Issue 48 (2022, 4)

- Issue 47 (2022, 3)

- Issue 46 (2022, 2)

- Issue 45 (2022, 1)

- Issue 44 (2021, 4)

- Issue 43 (2021, 3)

- Issue 42 (2021, 2)

- Issue 41 (2021, 1)

- Issue 40 (2020, 4)

- Issue 39 (2020, 3)

- Issue 38 (2020, 2)

- Issue 37 (2020, 1)

- Issue 36 (2019, 4)

- Issue 35 (2019, 3)

- Issue 34 (2019, 2)

- Issue 33 (2019, 1)

- Issue 32 (2018, 4)

- Issue 31 (2018, 3)

- Issue 30 (2018, 2)

- Issue 29 (2018, 1)

- Issue 28 (2017, 4)

- Issue 27 (2017, 3)

- Issue 26 (2017, 2)

- Issue 25 (2017, 1)

- Issue 24 (2016, 4)

- Issue 23 (2016, 3)

- Issue 22 (2016, 2)

- Issue 21 (2016, 1)

- Issue 20 (2015, 4)

- Issue 19 (2015, 3)

- Issue 18 (2015, 2)

- Issue 17 (2015, 1)

- Issue 16 (2014, 4)

- Issue 15 (2014, 3)

- Issue 14 (2014, 2)

- Issue 13 (2014, 1)

- Issue 12 (2013, 4)

- Issue 11 (2013, 3)

- Issue 10 (2013, 2)

- Issue 9 (2013, 1)

- Issue 8 (2012, 4)

- Issue 7 (2012, 3)

- Issue 6 (2012, 2)

- Issue 5 (2012, 1)

- Issue 4 (2011, 4)

- Issue 3 (2011, 3)

- Issue 2 (2011, 2)

- Issue 1 (2011, 1)

- Retracted articles

.png)